Original Article: JRCRS. 2025; 13(4):236-241

8- Impact of cervicogenic headache on work productivity: A Cross-Sectional Survey

Misbah binte Ilyas1, Tayyaba Iqbal2, Hifza Arif3, Nimra Ilyas bhutta4

1 Lecturer, Helping Hand Institute of Rehabilitation Sciences, Mansehra, Pakistan

2 Physiotherapist, Helping Hand Comprehensive Physical Rehabilitaion Program (HH CPRP), Pakistan

3 Teaching Assistant, Helping Hand Institute of Rehabilitation Sciences, Mansehra, Pakistan

4 Research In charge/ Clinical Supervisor, Helping Hand Institute of Rehabilitation Sciences, Mansehra, Pakistan

Full-Text PDF DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.53389/JRCRS.2025130408

ABSTRACT:

Background: One-sided, recurring headache that generally comes with neck pain and stiffness are associated with cervicogenic headache. These headaches have frequent episodes lately, and they alter people’s day to day routines and quality of work. It’s impossible to stay productive or focused while your head and neck is hurting continuously, and for healthcare professionals, it can even effect care services given to patients.

Objective: To assess the effect of cervicogenic headache on job performance among the office workers.

Methodology: Cross-sectional survey was implemented by the researchers, involving the Cervicogenic Headache International Study Group criteria to spot cases of cervicogenic headache. They Selected 290 volunteers using convenience sampling and focus on the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire (WPAI) to assess them. The researchers evaluated the data with SPSS version 22. Everyone who took part gave their informed consent.

Results: Age group selected in this study was among 27 – 40 years old. The results showed that the more hours of work each day causes the higher pain scores and shows elevation. Productivity and activity impairment scores also raise with pain. Absenteeism and presenteeism had somehow moderate association with pain (r = 0.408 and r = 0.519), but by giving a thorough look to work and activity impairment, the correlation was even stronger (r = 0.704 for both). Individuals having chronic CGH felt the strongest decline in their productivity, and the difference between all the stages of CGH it was clear that chronic cases had major worst impact (p < 0.001).

Conclusion: This study shows a significant correlation between cervicogenic headaches and lower work productivity. When the pain gets worse or lasts longer, job performance really takes a hit. But it’s not just about the pain itself

Keywords: Absenteeism, Cervicogenic headache, Neck pain headache, Presenteeism, Work productivity, Working population

Introduction:

Cervicogenic headache (CGH) was first described by Norwegian neurologist Ottar Sjaastad back in the early 1980s. It’s basically a headache that starts because of issues with the neck—problems in the cervical spine or the muscles and tissues around it.1, 2 The pain sticks around on one side and gets worse when you move your neck or head. CGH makes up about 15–20% of all chronic headaches, and it’s getting more common, especially now that so many jobs involve sitting for hours or putting constant strain on the neck.2-4

Headache problems in general particularly migraines and tension-type headaches (TTH) are among the most frequent neurological illnesses affecting working-age adults, with women being more afflicted. Globally, approximately half of all women report experiencing these types of headaches at some point in their lives.5

The CGH is more likely to cause discomfort specially physically, often causes functional limitations, absenteeism, presenteeism, and decreased productivity at work.4 Despite this, there is limited research that specifically examine the relationship between cervicogenic headache and work performance.6 Record of previous researches shows that they have focused on healthcare professionals, specifically nurses, leaving other occupational sectors yet to be explore more. This fact leads to represent a critical gap, as workers performing duties in various industries such as employees in office, workers in factories, and laborers who work manually are also at grave risk due to this type of occupational factors that includes poor workstation ergonomics, tasks repetition, heavy lifting, and sustained awkward postures for longer time.7

Another factor like prolonged mobile phone and computer use have been recognized as major contributors to cause forward head posture and strain in neck, these contributes to broader spectrum of risk factors at workplace that enhances musculoskeletal stress.8,9 Incompetent ergonomics, elevated job demands, and prolong working hours can further adds the risk of CGH symptoms, that leads to lower employees’ ability to concentrate, manage time effectively, and complete tasks on time with accuracy.10

Generally, headache affect up to 80–90% of the general population, within adults aging 18-65, approximately two-thirds of adult’s experience annually at least one episode.11 This causes not only compromises quality of life but also causes substantial damage to economic and societal costs which often leads to lost productivity. Particularly cervicogenic headache among chronic headache types, have prevalence ratio that is reported as 0.13% in men and 0.21% in women.2

Keeping in mind the increasing prevalence of CGH and its strong influence on quality of work performance, it becomes significant to have a closer view of how this condition effect the productivity in various occupational sectors. Reporting this research gap can help us in informing targeted interventions and also adds to improve ergonomics in workplaces and employee well-being.12, 13 Therefore, this particular study focuses on the evaluation of the impact of cervicogenic headache on work productivity focusing on absenteeism, presenteeism, job performance, and overall efficiency while keeping in view the importance of preventive measures and support on workplace to mitigate its effects.

Methodology

This study was conducted in the settings of Helping Hand Institute of Rehabilitation Sciences Trust Mansehra, with data collection taking place in Mansehra City. The study design employed was a cross-sectional survey to assess the impact of cervicogenic headache (CGH) on work productivity. The target population included individuals from the working population across different sectors in the city. The sample size recruited was n=290 cases with confirmed diagnosis of cervicogenic headache. Based on Fisher’s z approach for correlation, a sample of n= 270 was estimated, with 80% power to detect a minimum Pearson correlation of r ≈ 0.17 or higher (α = 0.05, two-tailed), with considering dropout rate of 0.1 the given sample was n= 300 through online sample size calculator of Fishers’ z transformation.

Inclusion criteria for the study required participants to be aged between 18- and 40-years office-based workers with a typical working schedule of 8 hours per day with variations above or below this threshold of either gender, and diagnosed with cervicogenic headache with symptoms persisting for more than 7 days either mild, moderate or severe intensity. Office based working population with average experience of approximately 5 years including full time or part time job durations comprising all occupations. Exclusion criteria included individuals with other types of headaches (such as tension-type headaches or migraines), cervical pathologies, systemic health issues, pregnant women, those with a history of spinal surgery, individuals with pre-diagnosed psychiatric conditions, and those with a history of substance abuse.

Participants were chosen using non-probability convenient sampling, which allowed for a diverse representation of the working population. The study was designed for the duration starting from October 2023 and ends at February 2024.

After getting ethical clearance from the Helping Hand Institute of Rehabilitation Sciences, under reference number HHIRS/REC/2025/0079 we started our research journey. Taking this approval was a sensitive initial step, as it justifies that our study also focuses to establish ethical standards and maintain the rights and well-being of all people involved. With this official approval, we move confidently to the next phase: identifying suitable volunteers for our study.

Participant selection was conducted fastidiously, using the Cervicogenic Headache International Study Group’s diagnostic criteria to evaluate individuals. This rigid screening process was important to ensure that only those who are clinically substantiated diagnosed for cervicogenic headache were included, thus adding to the validity and reliability of our findings. Before jumping to study procedures, we make sure to provide each selected participant with a proper guideline to the study’s objectives, methodology, and expected risks or benefits. We focused on the importance of voluntary

participation and carry out a question answers session to address any queries. After gaining fully informed, written consent we allow all the participants to proceed further, in line keeping in view ethical guidelines for research that involves humans as subjects.

In due course, a certified clinician performed a comprehensive assessment for each individual. This involves the Extension Rotation Test, a specialized clinical maneuver designed to differentiate between cervicogenic headache and vertebrobasilar insufficiency. By performing this test, we focused to lower the risk of misclassification and make sure that our participant cohort accurately represented the target population.

After making sure that all the participants met all inclusion criteria, they were given the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) questionnaire to solve. This proven instrument served to reach the extent to which cervicogenic headaches had affected their day to day functioning, productivity at work places, and engagement in routine activities. Keeping in view that some respondents might require clarification or guidance, we make sure our availability throughout this questionnaire process, offering support and guiding any queries to make sure accurate and complete responses. This direct engagement not only improved quality of data but also promoted a supportive research environment, that lead to encouraging honest and thoughtful participation by the individual. Through these carefully considered steps, we set the base for a robust and ethically sound investigation that showed the impact of cervicogenic headache.

We compiled the data and went through every filled and completed form. Two individuals couldn’t make it into the WPAI analysis due to the reason they weren’t working, so there was no work productivity left to measure. For the study, we used the WPAI questionnaire and the NPRS, the Numerical Pain Rating Scale. NPRS is pretty reliable and accurate, with reliability scores ranging from (r = 0.79 – 0.96).

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Version 22. After data collection, the normality of the data was tested with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, which showed the data to be non-parametric. Descriptive statistics summarized the demographic data. Due to the non-parametric nature of the data, Chi-Square and Spearman’s Correlation were used to assess the association between NPRS (Numeric pain rating scale) and the four WPAI (Work Productivity and Activity Impairment) scores. The Kruskal-Walli’s test was also applied to evaluate significant differences in WPAI scores across the three stages of pain.

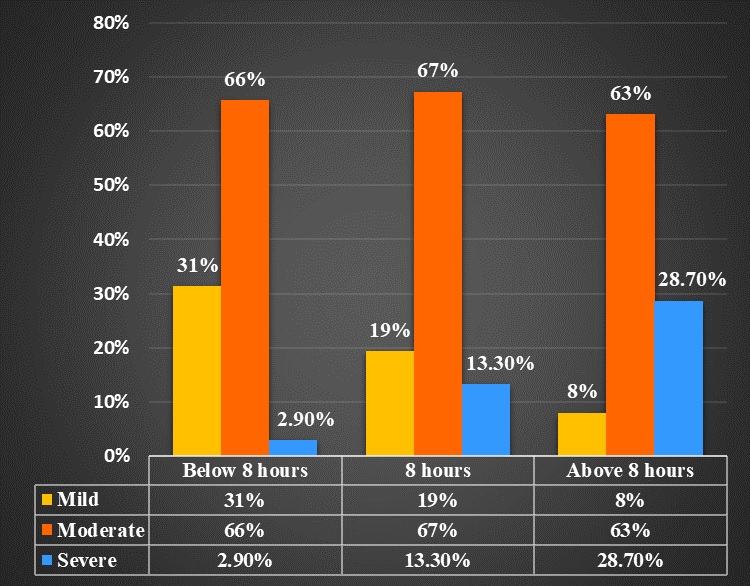

Figure 1: Association of CGH pain severity with working hours

Results

A total of n=290 office workers participated in the study with a mean age of 33.54±6.203 years. About n=196 (67.65) were male and n=94 (32.4%) were females. Basic demographics details are presented in table 1. About those with medical imaging, n=120(41.4%) have X-rays, n=31(10.7%) has MRI and n=38(13.1%) have both (X-ray and MRI) whereas, n=101(34.8%) were without any medical imaging.

The Median and interquartile ranges of WPAI scoring. For Q1, the median was 13 and the interquartile range was 10.7; for Q2, the median was 60 and the interquartile range was 30; for Q3, the median was 41.5 and the interquartile range was 24.7; and for Q4, the median was 60 and the interquartile range was 40. Out of 290 workers,59(20.3%) were suffered from mild pain, 190(65.5%) were suffered from moderate pain while 41(14.1%) suffered from severe pain. A total of n=221(76.2%) reported ongoing headache phase, n=56 (19.3%) reported a sub-intense stage, and n=13(4.5%) experienced an intense stage.

The association between working hours and NPRS. The results show that among all workers who works for less than 8 hours 31.4% had mild, 65.7% had moderate and 2.9% had severe pain. While among those who works for 8 hours 19.4% had mild, 67.3% had moderate and 13.3% had severe intensity of pain. While those who work for above 8 hours, 8% had mild, 63.2% had moderate and 28.7% had severe pain. In this case low p-value (<0.001) suggests that observed differences in NPRS level among the categories of working hours per day are statistically significant. This implies that there is likely a meaningful relationship between the levels of NPRS and working hours of workers in different workplaces. (Figure 1)

A non-parametric statistic, the Spearman Rho correlation analysis performed to measure the direction and strength between the Numeric rating scale and with each four WPAI (Work Productivity and Activity Impairment) Scoring. Spearman product correlation of Numeric rating scale and Percent work time missed due to health Q1 was found to be moderately positive (r=0.408) and statistically significant (p < .001). While there was also moderately positive correlation(r=0.519) between Q2 and Numeric rating Scale. While there was very low positive correlation (r=0.320) between Q3 and NRS. The main findings of this study showed that there was a significant positive correlation between the WPAI (Work Productivity and Activity Impairment) four scoring and Numeric pain rating scale but Q4 (activity impairment) of WPAI (Work Productivity and Activity Impairment) scoring had high positive correlation as compared to others. (Table 2).

The Kruskal–Wallis test showed statistically significant differences in all WPAI domains across pain severity groups (p < 0.001). Post-hoc Dunn’s tests revealed that participants with severe pain reported significantly higher absenteeism, presenteeism, overall work impairment, and activity impairment than those with moderate and mild pain (p < 0.001). This indicates a progressive negative impact of pain intensity on work productivity and daily functioning. (Table 3).

| Table 1: demographic detail | ||

| Variables | Frequency (%) | |

| Gender | Male | 196(67.6%) |

| Female | 94(32.4%) | |

| Qualification | SSc | 6(2.1%) |

| HSc | 17(5.9%) | |

| Honors | 162(55.9%) | |

| Masters | 100(34.5%) | |

| PhD | 5(1.7%) | |

| Employment status in years | Full time | 254(87.6%) |

| Part Time | 32(11%) | |

| Self Employed | 4(1.4%) | |

| Working Hours per day | Less than 8 hours | 191(65.9%) |

| 8 hours | 75(25.9%) | |

| More than 8 hours | 24(8.3%) | |

| Job Duration in years | Less than 1 year | 32 (11%) |

| 1 to 5 years | 133(45.9%) | |

| Above 5 years | 125(43.1%) | |

| Occupations | Health care professionals | 78(26.9%) |

| Computer -based workers | 80(27.6%) | |

| Teachers | 75(25.9%) | |

| Judiciary workers | 31(10.7%) | |

| Table:2 Correlation of WPAI (Work Productivity and Activity Impairment) and NPRS (Numeric pain rating scale) | ||

| WPAI | NPRS | |

| r-value | p-value | |

| Absenteeism | 0.408 | < 0.001 |

| Presenteeism | 0.519 | <0.001 |

| Work impairment | 0.320 | <0.001 |

| Activity impairment | 0.704 | <0.001 |

| Table 3: Kruskal Wallis test for comparison of Work productivity based on severity of pain. | |||||

| WPAI Domain | Mild CGH Pain

Median (IQR) |

Moderate CGH Pain

Median (IQR) |

Severe CGH Pain

Median (IQR) |

χ²

(df=2) |

p-value |

| Absenteeism | 14.29 (18.39) | 20.0 (19.04) | 27.82 (23.92) | 29.22 | < 0.001 |

| Presenteeism |

40.0 (40.0) |

50.0 (30.0) | 70.0 (27.5) | 18.79 | 0.03 |

| Overall Work Impairment | 33.3 (25.38) | 37.36 (19.62) | 42.12 (21.42) | 6.95 | 0.002 |

| Activity Impairment | 20.0 (20.0) | 40.0 (17.50) | 55.0 (30.0) | 140.95 | < 0.001 |

| CGH= cervicogenic headache, WPAI= work productivity and Impairment, χ²= chi-square | |||||

Discussion

This research focused to evaluate the cervicogenic headaches influence on work productivity in Mansehra City. We are the pioneers who looked at this problem here, specifically among workers of the offices. We selected 290 individuals from different jobs and evaluated carefully that how these headaches influence their work. Previously, Ernst MJ and colleagues (2023) conducted research that showed that office workers deal with headaches more often that may also lead to neck pain in most of them—around 80%. In the group we have focused, 27% of them have more computer working hours, which elaborates connection between cervicogenic headaches and staring at screens for long hours.14

In contrast to earlier findings, Javed MT et al. (2021) found a clear bridge between cervicogenic headaches and bad ergonomics. They really emphasizes on the point: better ergonomic habits can cut down on work problems caused by these headaches.15 The study also divided headache duration (acute, subacute, chronic), with chronic cases that showed the highest work impairment. This is compatible with research by Kristoffersen ES (2019) 16 and Rondinella S et al. (2023), confirming that chronic headaches lead to more workdays lost and greater absenteeism.17

The Cervicogenic Headache International Study Group criteria for diagnosis was selected and applied in this study, that shows a much more accurate diagnosis of cervicogenic headache as compare to the one according to the International Headache Society. Moreover, according to Kale K (2020), about 27% of healthcare workers suffered from cervicogenic headache, which negatively affected their productivity. In the last, the age segment of 18-40-year-olds was studied, and it was found that the age group most susceptible was between the ages of 18-25 years, which match with Jain H and Pachpute S’s study (2022 ).18

The effect on work productivity was calculated using the WPAI questionnaire, portraying strong correlations between work impairment and the pain severity. The analysis revealed that those with higher levels of pain tend to have greater losses in productivity. Moreover, cervicogenic headache sufferers had remarkably lower quality of life; these findings are consistent with the work of Mingels S (2021), Kasem SM et al. (2023).19

In the absence of a precise method to estimate working hours, it becomes almost impossible to evaluate how CGH impacts on productivity among the general population as a whole, including housewives and students. A modified WPAI (Work Productivity and Activity Impairment) questionnaire would need to define the effects of the phenomena. The HIT-6 (headache impact test-6) questionnaire could not possibly be included in this study, as its purpose is to measure how headaches may affect one’s daily life through pain intensity, functional limitations, fatigue, and concentration. However, the HIT-6 is self-reported headaches-related difficulties.19

The study conducted by Simić S. et al. in Novi Sad, Serbia, back in 2020, showed that migraines significantly reduce work efficiency. Participants with migraines reported the highest monthly work absenteeism, at 7.1%, versus individuals with tension-type headaches, at 2.23% (p=0.019), and all other types of headaches, at 2.15% (p=0.025).20

This research was into the effects of CGH and did not cover public education in preventative measures. It is therefore recommended that further research be conducted to increase awareness into posture, exercises, and ergonomic practices that will prevent such pains. Furthermore, studies should be conducted to educate the public on environmental triggers for cervicogenic headache and lessening their effects. Economic analyses are also indicated to quantify the loss to productivity caused by cervicogenic headache, which would justify effective management.

The practical applications of such studies would be the implementation of ergonomics in the workplace to avoid cervicogenic headaches and the organization of exercise workshops on posture correction and neck-strengthening exercises. Public awareness through various forms of media would also help in spreading the preventive strategies against cervicogenic headache.

Conclusion

This study focuses on the considerate impact of CGH on productivity of work and thus emphasizes the need for early identification and specific management. The proper management of musculoskeletal and sensitivity of pain that involves neck would minimize the occurrence of negative effects on job efficiency. Therefore it, constitutes an important aspect of workplace health and concerns regarding welfare, supporting the literature on cervicogenic headaches. In future, this could be studied in a multidimensional way using public awareness, education, and support systems to help improve productivity and quality of life.

References

- Bogduk N. Cervicogenic headache: anatomic basis and pathophysiologic mechanisms. Current pain and headache reports. 2001; 5:382-6.

- Sjaastad O, Fredriksen T. Cervicogenic headache: criteria, classification and epidemiology. Clinical and experimental rheumatology. 2000; 18:S-3.

- Cuenca-Leon E, Corominas R, Fernandez-Castillo N, Volpini V, Del Toro M, Roig M, et al. Genetic analysis of 27 Spanish patients with hemiplegic migraine, basilar-type migraine and childhood periodic syndromes. Cephalalgia. 2008; 28:1039-47.

- Jensen R, Stovner LJ. Epidemiology and comorbidity of headache. The Lancet Neurology. 2008; 7:354-61.

- Buse DC, Manack AN, Fanning KM, Serrano D, Reed ML, Turkel CC, et al. Chronic migraine prevalence, disability, and sociodemographic factors: results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention Study. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain. 2012; 52:1456-70.

- Hasselhorn HM, Ebener M, Vratzias A. Household income and retirement perspective among older workers in Germany—Findings from the lidA Cohort Study. journal of Occupational Health. 2020; 62: e12130.

- Hogg-Johnson S, van der Velde G, Carroll LJ, Holm LW, Cassidy JD, Guzman J, et al. The burden and determinants of neck pain in the general population: results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000–2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. Spine. 2008; 33: S39-S51.

- Gustafsson E, Johnson PW, Hagberg M. Thumb postures and physical loads during mobile phone use–A comparison of young adults with and without musculoskeletal symptoms. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology. 2010; 20:127-35.

- Neupane S, Ali U, Mathew A. Text neck syndrome-systematic review. Imperial journal of interdisciplinary research. 2017; 3:141-8.

- Korpinen L, Pääkkönen R, Gobba F, editors. Near Retirement Age (≥ 55 Years) Self-Reported Physical Symptoms and Use of Computers/Mobile Phones at Work and at Leisure. Healthcare; 2017: MDPI.

- Stovner LJ, Andree C. Prevalence of headache in Europe: a review for the Eurolight project. The journal of headache and pain. 2010; 11:289-99.

- Vetvik KG, MacGregor EA. Sex differences in the epidemiology, clinical features, and pathophysiology of migraine. The Lancet Neurology. 2017; 16:76-87.

- Hoy D, Protani M, De R, Buchbinder R. The epidemiology of neck pain. Best practice & research Clinical rheumatology. 2010; 24:783-92.

- Ernst MJ, Sax N, Meichtry A, Aegerter AM, Luomajoki H, Lüdtke K, et al. Cervical musculoskeletal impairments and pressure pain sensitivity in office workers with headache. Musculoskeletal science and practice. 2023; 66:102816.

- JAVED MTH, ANAM ABBAS FA, AFZAL R, MUNIR T, AZHAR S. Cervicogenic Headache among Young Adults Using Computers with more than 3 Hours of Screen Time. PJMHS Vol15, No-12. 2021.

- Kristoffersen ES, Stavem K, Lundqvist C, Russell MB. Impact of chronic headache on workdays, unemployment and disutility in the general population. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2019; 73:360-7.

- Rondinella S, Silipo DB. The effects of chronic migraine on labour productivity: Evidence from Italy. Labour. 2023; 37:1-32.

- Jain H, Pachpute S. Prevalence of Cervicogenic Headache in Computer Users. AIJR Abstracts. 2022:56.

- Kasem SM, Khodier RM, Fahim MK, Elsheikh MW. Quality of Life of Patients with Cervicogenic Headache: A Comparison with Migraine Patients without Aura Using MSQ v. 2.1 Questionnaire. Benha Medical Journal. 2023; 40:125-36.

- Simić S, Rabi-Žikić T, Villar JR, Calvo-Rolle JL, Simić D, Simić SD. Impact of individual headache types on the work and work efficiency of headache sufferers. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2020; 17:6918.

| Copyright Policy

All Articles are made available under a Creative Commons “Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International” license. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/). Copyrights on any open access article published by Journal Riphah college of Rehabilitation Science (JRCRS) are retained by the author(s). Authors retain the rights of free downloading/unlimited e-print of full text and sharing/disseminating the article without any restriction, by any means; provided the article is correctly cited. JRCRS does not allow commercial use of the articles published. All articles published represent the view of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of JRCRS. |