Original Article: JRCRS. 2025; 13(4):228-235

7- Associations Between Obesity, Piriformis Muscle Dysfunction, And Pain in Drivers: A Cross Sectional Study

Muhammad Salman1, Ramiz Meraj2, Usama Shahid3, Taimoor Ali Hassan4, Zohaib Hassan5, Waqas Haider Sial6, Muhammad Adnan Haider7

1 Physiotherapist, Spine C, Shanghai, China

2 Physiotherapist, Meraj physiotherapy Clinic, Burewala, Pakistan

3 Physiotherapist, Aqsa Clinic & maternity home Tandlianwala, Pakistan

4 Physiotherapist, Taimoor Physiotherapy and Health Clinic, Faisalabad, Pakistan

5 Physiotherapist, Hamza Hospital, Lahore, Pakistan

6 Physiotherapist, Royal Metropolitan medical university, Kyrgyzstan KG

7 MS Student, Physical Therapy Department, Tokyo Metropolitan University, Japan

Full-Text PDF DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.53389/JRCRS.2025130407

ABSTRACT:

Background: Obese vehicle drivers are predisposed to piriformis syndrome due to prolonged sitting, poor posture, and increased mechanical stress. Excess body weight may intensify piriformis muscle tightness and compress the sciatic nerve, resulting in chronic pain and functional limitations.

Objective: To determine the associations between obesity, piriformis muscle dysfunction, and pain severity among professional drivers.

Methodology: This cross-sectional study was conducted over six months in District Lahore among 113 male online vehicle drivers (Uber, Careem, Foodpanda) aged 18–60 years, selected through convenient sampling. Participants with prolonged sitting time and elevated BMI were included. Data were collected using a self-designed questionnaire, the Piriformis Stretch Test, and the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) for pain assessment. Ethical approval was obtained, and informed consent was secured from all participants. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 24.0, applying descriptive and Pearson’s correlation tests to evaluate relationships among BMI, Piriformis Stretch Test outcomes, and pain severity.

Results: A significant positive correlation was found between BMI and the Piriformis Stretch Test (r = 0.681, p < 0.001), indicating that drivers with higher BMI were more likely to exhibit piriformis tightness. Piriformis Stretch Test results also showed a strong correlation with pain intensity (r = 0.833, p < 0.001), while BMI correlated significantly with pain severity (r = 0.681, p < 0.001). Approximately 72% of participants reported moderate-to-severe pain (VAS > 5). Longer driving hours (>8 hours/day) and increasing age further amplified pain levels (p < 0.05).

Conclusion: Higher BMI, prolonged driving duration, and piriformis muscle dysfunction were significantly associated with increased pain severity among vehicle drivers. These findings highlight the importance of implementing targeted interventions such as weight management, ergonomic adjustments, and regular stretching programs to reduce musculoskeletal pain in this population.

Keywords: Correlation, Drivers, Obese, Occupational health, Piriformis dysfunction

Introduction:

Piriformis syndrome (PS) is a neuromuscular condition characterized by pain in the buttock that radiates down the lower limb due to compression or irritation of the sciatic nerve.¹ The piriformis muscle, a small but crucial external rotator and hip stabilizer, lies deep within the gluteal region and can entrap the sciatic nerve when it becomes tight, hypertrophied, or inflamed.² Anatomical variations, reported in 12–30% of individuals, such as the sciatic nerve passing through or around the piriformis, increase the likelihood of nerve compression.³

The prevalence of PS among individuals presenting with low back or leg pain has been estimated to range between 5% and 36%, according to clinical and imaging-based studies.⁴ The condition is frequently misdiagnosed due to symptom overlap with lumbar radiculopathy. Recent systematic reviews (2021–2023) emphasize that prolonged sitting, sedentary behavior, and repetitive microtrauma from occupational exposure are leading contributors to piriformis-related neuropathic pain.⁵

Occupational and lifestyle factors play a significant role in piriformis dysfunction. Professions involving sustained sitting—such as driving, banking, or office work—predispose individuals to chronic buttock and lower limb pain due to sustained hip flexion, reduced blood flow, and repetitive loading.⁶ Among these, professional drivers represent a particularly high-risk group, with reported symptom prevalence exceeding 75–80% in long-haul operators.⁷ Moreover, sitting posture, inadequate lumbar support, and vehicular vibrations have been identified as aggravating factors that increase sciatic nerve compression.⁸

Obesity is another critical and modifiable risk factor associated with piriformis syndrome. Excess body weight contributes to altered biomechanics, postural imbalances, and greater compressive forces on the lumbosacral and gluteal musculature.⁹ Recent meta-analyses have highlighted a significant relationship between elevated Body Mass Index (BMI) and the incidence of musculoskeletal pain syndromes, particularly in regions prone to mechanical stress such as the lower back and hips.¹⁰ Obesity-induced inflammation and soft tissue strain may exacerbate piriformis muscle tightness, increasing the likelihood of nerve irritation and pain.¹¹

Despite these associations, the combined effects of BMI, occupational sitting duration, and piriformis muscle dysfunction have not been adequately explored in occupational drivers, especially in South Asian populations. Most existing studies focus on either obesity or sedentary occupation as independent factors, leaving a gap in understanding how these variables interact to influence pain severity and functional impairment.

Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate the associations between BMI, piriformis muscle dysfunction (as assessed by the Piriformis Stretch Test), and pain severity among professional vehicle drivers. By identifying modifiable risk factors, the findings could inform preventive strategies, ergonomic interventions, and physiotherapy-based rehabilitation programs tailored for high-risk occupational groups.

Methodology

This study comprised a cross-sectional survey design (Reference No. FIHS/RW/LHR/252) conducted in District Lahore, focusing on online vehicle drivers employed by Uber, Careem, and Foodpanda. The sample size (N = 113) was determined based on convenience sampling; however, a post-hoc power analysis was conducted using G*Power 3.1. With an alpha of 0.05 and an observed effect size of r = 0.68, the achieved power (1–β) was 0.99, indicating that the sample was adequately powered to detect moderate to large correlations.12 The male participants aged 18–60 years were recruited through convenient sampling over a six-month period, following approval of the research synopsis. While convenient sampling facilitated access to a hard-to-reach occupational group, it is acknowledged as a methodological limitation due to potential sampling bias and limited generalizability of findings.

Included adult males aged 18–60 years with a Body Mass Index (BMI) ≥ 25 kg/m² and a minimum of 6 hours of sitting time per workday. Participants were categorized using WHO BMI classifications: overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m²), obese class I (30.0–34.9 kg/m²), and obese class II (>35.0 kg/m²).13 Individuals with a history of spinal or lower limb surgery, spinal deformity, neurological disorder, cardiovascular disease, or recent musculoskeletal injury were excluded.

A self-designed and pre-validated questionnaire was used for data collection. The tool was pilot-tested on 35 drivers from the same occupational group to ensure face and content validity. In addition to the questionnaire, the Piriformis Stretch Test (PST) was administered to evaluate piriformis muscle dysfunction. The PST was performed by a licensed physiotherapist with over five years of clinical experience. The participant was positioned supine, and the hip and knee were flexed to 90 degrees; the examiner then adducted and internally rotated the hip to stretch the piriformis.14 The test was considered positive if the maneuver reproduced gluteal pain or radiating symptoms along the sciatic distribution.

To minimize examiner bias, all assessments were performed by the same examiner who was blinded to the participants’ BMI category and pain score. The same standardized protocol and testing environment were maintained for all subjects. Pain intensity was measured using the Visual Analog Scale (VAS), ranging from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst imaginable pain).

The study was conducted in accordance with ethical research principles, ensuring voluntary participation, confidentiality, and informed consent from all participants prior to data collection. Approval was obtained from the institutional ethics committee, and participants were assured of data privacy and the right to withdraw at any stage.

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 24.0. Descriptive statistics (frequencies, means, and standard deviations) were calculated, and Pearson’s correlation analysis was applied to determine associations among BMI, Piriformis Stretch Test results, and pain intensity. Although only correlation analysis was conducted in this study, future research should include regression or multivariate models to control for confounding factors such as age, driving hours, and physical activity, thereby strengthening causal inference.

Ethical considerations were strictly observed, with formal approval from the institutional review board and adherence to the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants were ensured anonymity and were not subjected to any physical or psychological risk.

Results

The participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 60 years (mean ± SD = 32.33 ± 1.02 years), with the highest proportion falling in the 36–45-year age group, which is known to be more prone to Piriformis Syndrome (PS). The mean height and weight were 166.20 ± 14.26 cm and 55.07 ± 8.52 kg, respectively, indicating considerable variation in body size among the drivers.

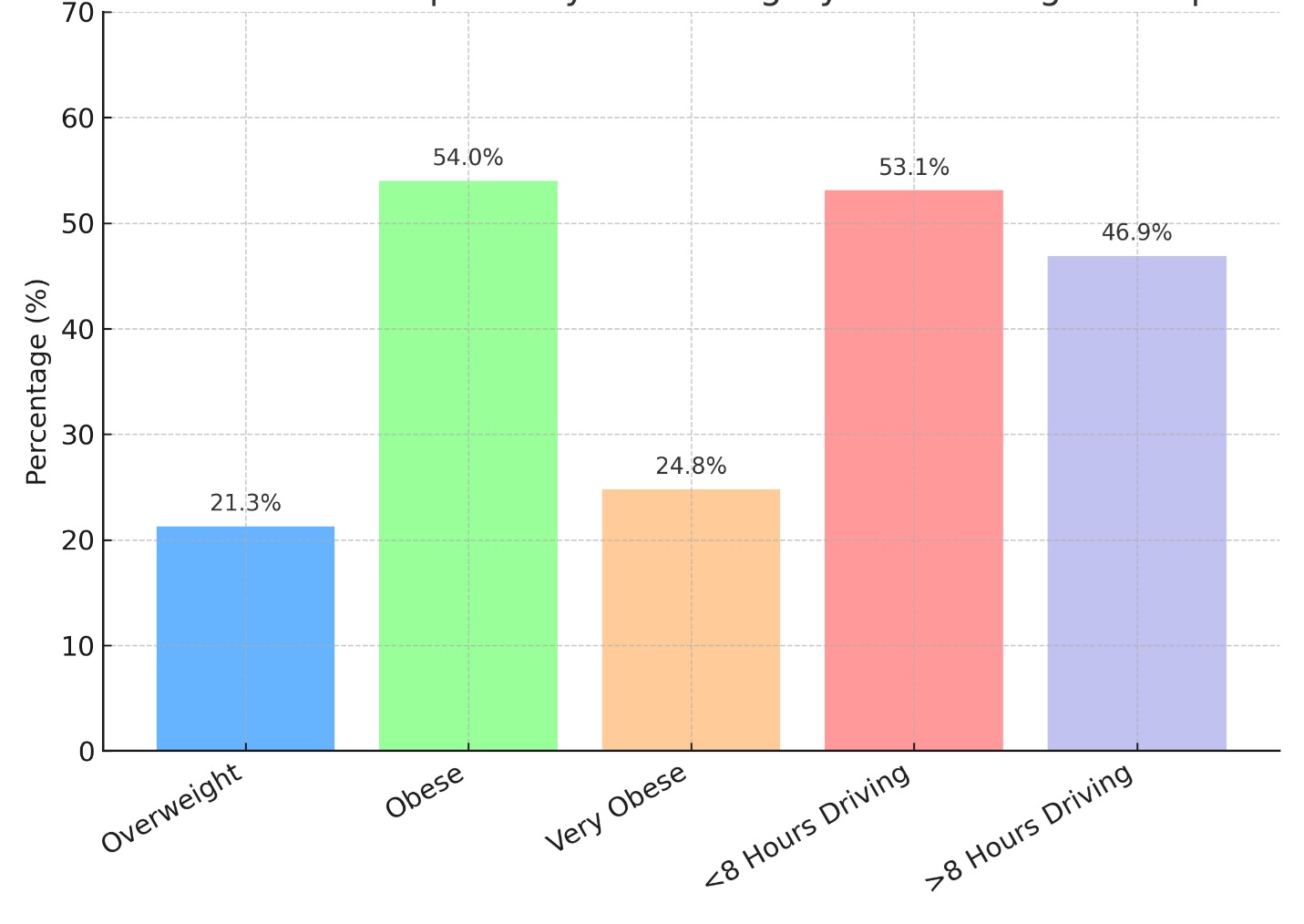

Based on Body Mass Index (BMI) classification, more than half of the participants were found to be obese, with a notable proportion categorized as very obese. This pattern suggests that excess body weight may contribute to greater mechanical loading on the spine and lower limbs, potentially increasing the risk of developing PS and related musculoskeletal disorders.

Regarding occupational exposure, nearly half of the participants reported driving for more than eight hours per day. Extended sitting duration, especially with poor posture, was found to be associated with a higher prevalence of discomfort and pain symptoms related to PS. These findings highlight the potential interaction between prolonged sitting, excess body weight, and the development of piriformis-related musculoskeletal problems.

| Table 1: Demographic Characteristics of the Study Population | |||

| Variable | Category | Frequency (N) | Percent (%) |

| Age Group (Years) | Mean ± SD | 32.33±.1.022 | – |

| Height (cm) | 166.2 ± 14.26 | – | |

| Weight (kg) | 55.07 ± 8.52 | – | |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | Overweight | 24 | 21.26% |

| Obese | 61 | 53.98% | |

| Very Obese | 28 | 24.77% | |

| Driving Hours Per Day | <8 Hours | 60 | 53.1% |

| >8 Hours | 53 | 46.9% | |

Figure 1: Distribution of Body Mass Index (BMI) Categories and Driving Hours per Day Among Participants

The visualization highlights a higher prevalence of obesity among individuals who reported longer driving hours, suggesting a potential relationship between sedentary occupational exposure and increased body mass index.

Out of 113 online vehicle drivers who participated in this study, 41.5% reported experiencing pain during driving, while 58.4% reported no pain. Analysis of pain severity using the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) revealed that 14.2% of participants had no pain, 16.8% reported mild pain, 13.3% experienced moderate pain, 38.1% experienced severe pain, and 17.7% reported their pain as the worst possible. These results indicate that a substantial proportion of the study population experienced moderate to severe pain, emphasizing the burden of musculoskeletal discomfort associated with prolonged sitting and occupational strain.

When examining Piriformis Stretch Test outcomes, 27% of participants tested positive, suggesting the presence of piriformis muscle tightness or dysfunction, while 72.5% tested negative. This distribution indicates that approximately one in four drivers exhibited physical signs consistent with Piriformis Syndrome (PS).

Further analysis revealed important age-related and occupational associations with pain severity. Among participants aged 18–25 years, 64.5% reported severe pain, while none reported the worst pain category, suggesting an early manifestation of discomfort in younger drivers. In contrast, drivers aged 46–60 years demonstrated a higher prevalence of worst pain (53%), illustrating a clear age-related progression of pain severity. Middle-aged drivers (36–45 years) also exhibited substantial musculoskeletal strain, with roughly one-third of this group experiencing either moderate (31.5%) or worst pain (31.5%). These findings underscore how advancing age and occupational exposure amplify the risk and intensity of pain symptoms among long-term drivers.

Daily driving duration was another significant factor. Drivers who worked less than 8 hours per day reported relatively lower pain intensity, with 26.6% experiencing no pain and only 37% reporting severe pain. Conversely, none of the participants driving more than 8 hours per day reported being pain-free; instead, 77% of these drivers experienced severe or worst pain levels. These results establish a clear relationship between prolonged sitting duration and increased pain severity, likely due to sustained muscle tension, nerve compression, and poor ergonomic posture during long driving hours.

In summary, Table 2 highlights that pain prevalence and intensity increased with both age and driving duration, while nearly one-quarter of drivers exhibited piriformis muscle dysfunction. This pattern suggests that musculoskeletal disorders like Piriformis Syndrome may arise from the combined effects of prolonged sitting, occupational posture, and body composition.

Correlation analyses were conducted to explore the relationships among BMI, Piriformis Stretch Test outcomes, and pain severity (VAS scores). Prior to analysis, data were assessed for normality (using the Shapiro–Wilk test) and linearity (via scatterplot inspection). All variables demonstrated approximately normal distributions and linear associations, meeting the assumptions required for Pearson’s product-moment correlation.

Results revealed a strong positive correlation between BMI and Piriformis Stretch Test results (r = 0.681, p < 0.001), indicating that drivers with higher body mass indices were significantly more likely to test positive for piriformis muscle tightness or dysfunction. This suggests that excessive adiposity contributes to altered biomechanics and increased mechanical loading around the pelvic and gluteal regions, thereby predisposing obese individuals to Piriformis Syndrome.

A similarly strong correlation was found between Piriformis Stretch Test results and pain severity (r = 0.833, p<0.001), suggesting that participants with confirmed piriformis dysfunction were substantially more likely to report higher levels of pain. This relationship underscores the central role of the piriformis muscle in mediating sciatic nerve irritation and related musculoskeletal discomfort among drivers.

Additionally, a significant positive relationship was observed between BMI and pain severity (r = 0.681, p<0.001), reinforcing the notion that higher body weight is directly associated with increased pain perception. This may be due to greater compressive forces on the spine and hip region in obese drivers, leading to cumulative muscle strain and nerve compression over time.

To ensure robustness, non-parametric Spearman’s rho correlations were also computed because the Piriformis Stretch Test variable was ordinal. The Spearman’s coefficients remained consistent with the Pearson’s results: BMI–Piriformis (ρ = 0.64, p < 0.001), Piriformis–Pain (ρ=0.81, p < 0.001), and BMI–Pain (ρ = 0.66, p < 0.001). This parallel outcome confirms that the associations were strong and not affected by data distribution type.

To address potential confounding, partial correlation analyses were conducted while controlling for age and driving hours—both significant occupational and demographic variables. The correlations remained significant, though slightly attenuated: BMI–Piriformis (r=0.611, p < 0.001) and Piriformis–Pain (r = 0.792, p<0.001). These results demonstrate that the observed associations were independent of age or work duration, highlighting intrinsic biomechanical and physiological links between obesity, muscle dysfunction, and pain.

In summary, BMI, piriformis muscle dysfunction, and pain intensity are strongly interrelated, even after accounting for age and occupational exposure. The findings emphasize that obesity and prolonged sitting act synergistically, contributing to muscle compression, nerve irritation, and pain severity among professional drivers. These results advocate for preventive interventions such as weight management, ergonomic correction, and targeted stretching programs to alleviate piriformis-related pain in this high-risk occupational group.

| Table 2: Distribution of Pain Experience, Severity, Piriformis Stretch Test Results, and Their Associations with Age and Driving Hours | |||

| Variable | Category | Frequency (N) | Percent (%) |

| Pain during Driving | Yes | 47 | 41.5% |

| No | 66 | 58.4% | |

| Severity of Pain (VAS) | No pain | 16 | 14.2% |

| Mild pain | 19 | 16.8% | |

| Moderate pain | 15 | 13.3% | |

| Severe pain | 43 | 38.1% | |

| Worst pain | 20 | 17.7% | |

| Piriformis Stretch Test | Positive | 31 | 27% |

| Negative | 82 | 72.5% | |

| Age & Severity of Pain | 18-25 years | No pain: 5 (16%) | Severe pain: 20 (64.5%) |

| Mild pain: 6 (19%) | Worst pain: 0 (0%) | ||

| 26-35 years | No pain: 11 (38%) | Mild pain: 13 (44.8%) | |

| Mild pain: 13 (44.8%) | Moderate pain: 3 (10.3%) | ||

| Severe pain: 2 (7%) | |||

| 36-45 years | Moderate pain: 12 (31.5%) | Severe pain: 14 (36.8%) | |

| Worst pain: 12 (31.5%) | |||

| 46-60 years | Severe pain: 7 (46.6%) | Worst pain: 8 (53%) | |

| Driving Hours & Severity of Pain | <8 hours | No pain: 16 (26.6%) | Severe pain: 22 (37%) |

| Mild pain: 19 (31.6%) | Worst pain: 0 (0%) | ||

| >8 hours | No pain: 0 (0%) | Severe pain: 21 (39%) | |

| Moderate pain: 12 (22.6%) | Worst pain: 20 (38%) | ||

| Pain Experience, Severity, and Associations with Age and Driving Hours (Based on Table 2) | |||

| Table 3: Association Between Piriformis Stretch Test, Body Mass Index, and Pain: A Correlational Analysis | |||

| Correlations | Piriformis Stretch Test | Body Mass Index (BMI) | Pain |

| Piriformis Stretch Test | Pearson Correlation | 1 | 0.681** |

| p value | – | <0.001 | |

| N | 113 | 113 | |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | Pearson Correlation | 0.681** | 1 |

| p value | <0.001 | – | |

| N | 113 | 113 | |

| Pain | Pearson Correlation | 0.833** | – |

| p value | <0.001 | – | |

| N | 113 | – | |

Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine the relationship between the Piriformis Stretch Test, BMI, and pain severity. Specifically, the objective was to determine whether individuals with higher BMI values were more likely to yield a positive Piriformis Stretch Test and experience greater pain intensity due to potential muscle dysfunction. The primary variables analyzed were BMI, Piriformis Stretch Test results, and reported pain levels.

Statistical analysis revealed a strong positive correlation between BMI and the Piriformis Stretch Test (r = 0.681, p<0.001), indicating that individuals with higher BMI were more likely to exhibit piriformis tightness or dysfunction. Similarly, the Piriformis Stretch Test showed a strong correlation with pain severity (r = 0.833, p < 0.001), signifying that those testing positive experienced more pronounced pain. BMI also demonstrated a significant relationship with pain intensity (r=0.681, p < 0.001), suggesting that excess body weight may contribute to pain severity through increased mechanical loading and musculoskeletal strain.

These findings align with previous studies highlighting the association between elevated BMI and musculoskeletal disorders. Wearing et al. reported that excessive mechanical stress on soft tissues and joints from high body weight contributes to tightening and pain, particularly in weight-bearing structures.15,16 Similarly, Karadag-Saygi et al. observed a positive association between higher BMI and muscle tightening in individuals with lower limb dysfunction.17 The present results also corroborate the observations of Stecco et al., who linked myofascial restrictions and obesity with heightened pain sensitivity.18

The strong correlation between the Piriformis Stretch Test and pain in this study supports the findings of Hopayian et al., who identified piriformis syndrome as a prevalent cause of sciatic pain aggravated by prolonged sitting and biomechanical imbalances.19 Fishman et al. also noted that patients with positive Piriformis Stretch Tests frequently reported significant pain and functional limitations.20 Moreover, Tonley et al. emphasized that piriformis tightness disrupts hip mechanics and intensifies pain in overweight individuals.21,22

The relationship between BMI and pain severity is well documented in literature. Stovitz et al. demonstrated that individuals with higher BMI are more likely to report chronic musculoskeletal pain due to inflammatory processes and joint overload.23 Vincent and colleagues attributed this to adipose tissue-induced systemic inflammation, altering pain perception.24 Krishnan et al. further suggested that obesity-related biomechanical alterations can cause muscle stiffness, reduced flexibility, and increased pain sensitivity.25

In addition, Benzon et al. highlighted that piriformis tightness can compress the sciatic nerve, aggravating pain symptoms,26 while Boyajian-O’Neill et al. reported that individuals with elevated BMI are more prone to piriformis syndrome due to increased pressure on the sciatic nerve and adjacent tissues.27 Beales et al. recommended that weight management, combined with targeted stretching and strengthening, may improve symptoms,28 an implication consistent with the findings of the present study.

Overall, the study reinforces emerging evidence linking elevated BMI with piriformis muscle dysfunction and increased pain severity. These findings underscore the importance of preventive and rehabilitative strategies such as weight management, ergonomic interventions, posture correction, and specific exercise programs to alleviate musculoskeletal discomfort among individuals with higher BMI and piriformis-related pain.

Limitations: This study has several limitations. The relatively small sample size and cross-sectional design limit causal inference. Additionally, self-reported data (e.g., driving hours) may introduce reporting bias, and the exclusion of female participants restricts generalizability. Future research should include larger, more diverse samples and adopt longitudinal designs to better understand causative mechanisms and rehabilitation outcomes related to piriformis dysfunction in overweight populations.

Clinical Implications: From a clinical perspective, these findings emphasize the importance of ergonomic modifications for prolonged sitting, incorporation of piriformis stretching routines, and structured weight management programs. Tailored exercise interventions focusing on flexibility and core strengthening may help reduce the prevalence and severity of piriformis-related pain in individuals with higher BMI.

In summary, this study contributes to the growing body of evidence linking BMI to piriformis muscle dysfunction and pain intensity, highlighting the need for multidisciplinary approaches integrating physiotherapy, ergonomic management, and weight control strategies.

Conclusion

This study concluded a significant association between prolonged driving hours, elevated body mass index, and increased severity of piriformis-related pain among vehicle drivers. The strong correlations between BMI, pain severity, and piriformis muscle involvement suggest that sedentary occupational exposure contributes to musculoskeletal dysfunction. These findings highlight the need for preventive ergonomic strategies and weight management interventions to reduce the risk of piriformis syndrome in professional drivers.

References

- Pande A, Gopinath RA, Ali S, Adithyan R, Pandian S, Ghosh S. Piriformis Syndrome and Variants–A Comprehensive Review on Diagnosis and Treatment. Journal of Spinal Surgery. 2021 Oct 1;8(4):7-14.

- Larionov A, Yotovski P, Filgueira L. Novel anatomical findings with implications on the etiology of the piriformis syndrome. Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy. 2022 Oct;44(10):1397-407.

- BUILDER V. Neurologic Pathologies and Disorders. Mosby’s Pathology for Massage Professionals-E-Book: Mosby’s Pathology for Massage Professionals-E-Book. 2021 Sep 5:172.

- Bhattacharya S, Garg S, Grover A, Singh A. Credit carditis or fat wallet syndrome-A neglected yet, preventable public health problem. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care. 2024 Apr 1;13(4):1566-7.

- Zenda KP. Understanding the Ergonomic Factors Associated with Lower Back Pain Amongst Mining Employees: A Case Study of Trojan Nickel Mine. University of Johannesburg (South Africa); 2023.

- Iranmanesh M, Shafiei Nikou S, Saadatian A, Alimoradi M, Khalaji H, Monfaredian O, Saki F, Konrad A. The training and detraining effects of 8-week dynamic stretching of hip flexors on hip range of motion, pain, and physical performance in male professional football players with low back pain. A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Sports Sciences. 2025 Jun 6:1-5.

- Muhammad A, Rana MR, Amin T, Angela C, Pereira FA, Bhutto MA. Prevalence of Piriformis Muscle Tightness among Undergraduate Medical Students. Pakistan Journal of Medical & Health Sciences. 2022 Apr 7;16(02):964-.

- Salam A, Khalid A, Waseem I, Mahmood T, Mahmood W. Comparison Between Effects Of Passive Versus Self-Mobilization Of Sciatic Nerve In Piriformis Syndrome For Relieving Pain And Improving Hip Outcomes: soi: 21-2017/re-trjvol06iss01p298. The Rehabilitation Journal. 2022 Mar 31;6(01):298-302.

- Hill L, Brandon K. Musculoskeletal Assessment for Patients with Pelvic Pain. Management of Chronic Pelvic Pain: A Practical Manual. 2021 Mar 25:33.

- Linck G, Boissonnault B. Symptom Investigation: Screening for Medical Conditions. InFoundations of Orthopedic Physical Therapy 2024 Jun 1 (pp. 80-104). Routledge.

- Sharif S, Ali MY, Kirazlı Y, Vlok I, Zygourakis C, Zileli M. Acute back pain: The role of medication, physical medicine and rehabilitation: WFNS spine committee recommendations. World Neurosurgery: X. 2024 Mar 6:100273.

- Serdar CC, Cihan M, Yücel D, Serdar MA. Sample size, power and effect size revisited: simplified and practical approaches in pre-clinical, clinical and laboratory studies. Biochemia medica. 2021 Feb 15;31(1):27-53.

- Girard L, Djemili F, Devineau M, Gonzalez C, Puech B, Valance D, Renou A, Dubois G, Braunberger E, Allou N, Allyn J. Effect of body mass index on the clinical outcomes of adult patients treated with venoarterial ECMO for cardiogenic shock. Journal of Cardiothoracic and Vascular Anesthesia. 2022 Aug 1;36(8):2376-84.

- Othman IK, Raj NB, Siew Kuan C, Sidek S, Wong LS, Djearamane S, Loganathan A, Selvaraj S. Association of piriformis thickness, hip muscle strength, and low back pain patients with and without piriformis syndrome in Malaysia. Life. 2023 May 18;13(5):1208.

- Choudhari A, Gupta AK, Kumar A, Kumar A, Gupta A, Chowdhury N, Kumar A. Wear and friction mechanism study in knee and hip rehabilitation: A comprehensive review. Applications of biotribology in biomedical systems. 2024 Jun 30:345-432.

- Adouni M, Aydelik H, Faisal TR, Hajji R. The effect of body weight on the knee joint biomechanics based on subject-specific finite element-musculoskeletal approach. Scientific Reports. 2024 Jun 14;14(1):13777.

- Tahran Ö, Ersoz Huseyinsinoglu B, Yolcu GÜ, Karadağ Saygı E, Yeldan İ. Comparing face-to-face and internet-based basic body awareness therapy for fibromyalgia: a randomized controlled trial. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2025 Feb 19:1-2.

- Bonaldi L, Berardo A, Stecco A, Stecco C, Fontanella CG. Assessment of the Fascial System Thickness in Patients with and Without Low Back Pain: A Narrative Review. Diagnostics. 2025 Aug 16;15(16):2059.

- Faryad I, Khalid F, Munawar A, Iqbal MH, Anwar A. Prevalence of Piriformis Syndrome among Tailoring Professionals and its Association with Prolong Sitting. Journal of Health, Wellness and Community Research. 2025 Jul 14: e482-.

- Aroob Z, Bashir MS, Noor R, Ikram M, Ramzan F, Naseer A, Sabir N. Comparative effects of fascial distortion model with and without neuromuscular inhibition technique on pain, range of motion and quality of life in patients with piriformis syndrome. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2025 Apr 24;47(9):2378-83.

- Powell J, Kent T, Hanson C. Dysfunction, Evaluation, Diagnosis, and Treatment of the Hip Complex: Nonsurgical and Surgical. Foundations of Orthopedic Physical Therapy. 2024 Jun 1:211-36.

- Prentice WE. Understanding and managing the healing process through rehabilitation. InRehabilitation Techniques for Sports Medicine and Athletic Training 2024 Jun 1 (pp. 23-56). Routledge.

- Cárdenas-Sandoval RP, Pastrana-Rendón HF, Avila A, Ramírez-Martínez AM, Navarrete-Jimenez ML, Ondo-Mendez AO, Garzón-Alvarado DA. Effect of therapeutic ultrasound on the mechanical and biological properties of fibroblasts. Regenerative Engineering and Translational Medicine. 2023 Jun;9(2):263-78.

- Spencer L. Investigation of the Metabolic Effects of Liraglutide on Patients with Overweight and Obesity. University of Derby (United Kingdom); 2023.

- Adouni M, Aydelik H, Faisal TR, Hajji R. The effect of body weight on the knee joint biomechanics based on subject-specific finite element-musculoskeletal approach. Scientific Reports. 2024 Jun 14;14(1):13777.

- Benzon HT, Katz JA, Benzon HA, Iqbal MS. Piriformis syndrome: Anatomic considerations, diagnosis, and treatment. Anesthesiology Clinics. 2013;31(2):247-260.

- Othman IK, Raj NB, Siew Kuan C, Sidek S, Wong LS, Djearamane S, Loganathan A, Selvaraj S. Association of piriformis thickness, hip muscle strength, and low back pain patients with and without piriformis syndrome in Malaysia. Life. 2023 May 18;13(5):1208.

- Beals JW, Kayser BD, Smith GI, Schweitzer GG, Kirbach K, Kearney ML, Yoshino J, Rahman G, Knight R, Patterson BW, Klein S. Dietary weight loss-induced improvements in metabolic function are enhanced by exercise in people with obesity and prediabetes. Nature metabolism. 2023 Jul;5(7):1221-35.

| Copyright Policy

All Articles are made available under a Creative Commons “Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International” license. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/). Copyrights on any open access article published by Journal Riphah college of Rehabilitation Science (JRCRS) are retained by the author(s). Authors retain the rights of free downloading/unlimited e-print of full text and sharing/disseminating the article without any restriction, by any means; provided the article is correctly cited. JRCRS does not allow commercial use of the articles published. All articles published represent the view of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of JRCRS. |