Original Article: JRCRS. 2025; 13(4):221-227

6- Effectiveness of Individual Narrative Therapy with Specialized Adaptations in Children with Intellectual Disability: Pre-Post Experimental Study

Maham Ikram1, Nayab Iftikhar2

1 Speech Language Pathologist, Centre for Clinical Psychology, University of Punjab, Lahore, Pakistan

2 Assistant Professor, Centre for Clinical Psychology, University of Punjab, Lahore, Pakistan

Full-Text PDF DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.53389/JRCRS.2025130406

ABSTRACT:

Background: The present study analyzed the effectiveness of Narrative Therapy in developing narrative proficiency in Children with Intellectual Disabilities.

Objective: To determine the effect of story retelling and narrative comprehension with Narrative Therapy in children with Intellectual Disability

Methodology: The study employed a within-subjects design. The study sample included participants diagnosed with a mild level of Intellectual Disability. The study involved ten participants (N = 10), comprising five males and five females, whose mental age ranged from four to six years. The sample was recruited using a nonprobability purposive sampling technique from Amin Maktab and Rising Angel’s institutes in Lahore from January 2023 to January 2024. Multilingual Assessment Intervention for Narratives (MAIN) assessed story retelling and comprehension. The therapy lasted for eight weeks. Each participant had twenty-four sessions of intervention.

Results: The data were analyzed using the Wilcoxon signed rank test and frequency graphs to report the pre- and post-evaluation scores. The results, which included macrostructural and microstructural analyses, showed a marked improvement in narrative abilities post-intervention, with p < 0.05.

Conclusion: The study’s findings, which revealed a significant increase in story retelling and comprehension scores of narratives after the intervention, underscore the effectiveness of narrative therapy in developing narration abilities in children with Intellectual Disability.

Keywords: Narrative Therapy, Intellectual Disability, Microstructure, Macrostructure

Introduction:

Narratives are functional skills for sharing stories about single or related events.1 Katz-Bernstein and Schroder define narrative as follows: “Narratives contain unique events that contain a special feature, in the form that something unexpected has happened. Quite essential for narration, in contrast to reporting, is that with the unexpected, the breaking of the plan, an emotional evaluation accompanies it. An important function of narrative is to convey this emotion to the listener.2,3 Labov first explored narratives as analytical tools in 2013. They are considered cultural instruments that convey information about historical events in a manner accepted within a given culture.4 Narrative ability is essential for building friendships and fitting in with peers.5 A conventional narrative structure typically includes four components: an abstract, orientation, complicated action, and coda.4 According to one widely adopted model (Stein & Glenn, 1979), narration relies on both microstructure (e.g., vocabulary and syntax) and macrostructure (e.g., story structure).6 Narrative production requires assumptions about the character’s goals, her attempts to achieve these goals, and the outcomes of those attempts.7 According to a study fictional narratives are more commonly employed by speech-language pathologists in actual clinical practice for assessing children’s language abilities than personal narratives.8 Michael White and David Epston first introduced Narrative Therapy in the 1980s. The approach is built on a simple yet powerful idea that individuals make sense of their lives through the stories they tell about themselves. When these stories become dominated by problems, they can limit how people see their identity and choices. Narrative Therapy helps individuals step back, question these problem-focused accounts, and gradually reshape them into more hopeful, strength-based stories that highlight resilience and possibility.9

Petersen (2010) described narrative intervention as an approach that utilizes oral narratives as the mode of communication, within which clinicians model language-based features to support participant practice.10 The stories associated with a series of pictures are usually modeled and slowly fade so that participants can independently retell the story by the end of the intervention.11 Intervention strategies include focused stimulation, scaffolding, and dialogic reading to target micro- and macrostructure elements. Children can narrate their own stories by engaging in storytelling with felt, utilizing all their senses.12 Therapeutic play with children has long been recognized as an effective clinical intervention.13 A researcher investigated how students with intellectual disabilities tell stories. It was an examination of Narrative Macrostructure and Microstructure. The study analyzed the narratives of 17 adult students with intellectual disabilities and 16 typically developing students in terms of microstructure (e.g., length, lexis, grammaticality, and complexity), macrostructure (e.g., goals, attempts, and outcomes), and internal state terms (ISTs). The findings revealed that while adults with intellectual disabilities showed weaknesses in coherence, syntactic complexity, and grammatical sentence production, they demonstrated notable strengths in narrative macrostructure, story schema, and ISTs. The study also suggested that as adults with intellectual disabilities age, their narrative performance improves, likely due to maturity, life experiences, and indirect environmental exposure.14

A Study was conducted to examine the experiences of children with developmental disabilities and their families through narrative therapy, demonstrating its effectiveness in various contexts.15

A research was conducted on cognitive and linguistic effects of narrative-based language intervention in children with Developmental Language Disorder. Ten children (8–11 years old) with DLD completed 15 sessions of narrative-based language intervention. Results of single-subject data revealed improvements in language for five participants. An additional four participants improved on a working memory probe only. On standardized measures, clinically significant gains were noted for one additional participant on a language measure and one additional participant on a visuospatial working memory measure.16

A research was conducted a study to examine the effect of storytelling on verbal language in children with autism spectrum disorder. The sample included twenty children aged four to seven years. Thirty stories suitable for children aged three to seven years were selected and narrated daily for 30 minutes. The findings, calculated using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test and Wilcoxon test, suggested that storytelling can enhance imagination and promote the development of verbal language in children with Autism Spectrum Disorder.17

The present study aimed to investigate the effectiveness of narrative therapy in developing narrative proficiency in children with intellectual disability. The study used a narrative intervention program called Supporting Knowledge in Language and Literacy. The basic concept of the SKILL program is that two crucial elements of narration that are cognitive and linguistics, are essential for achieving the following three outcomes: (1) Enhancing the proficiency to remember important ideas and particular details from oral and written text, (2) improving students’ capacity to form stories with cohesive and coherent complex structures, (3) understanding new knowledge in narrative genre and enhancing metacognitive skills.18 Targeting the use of mental state and causal language can lead to positive improvements in narrative production for children with intellectual disability.19

The study specifically analysed narratives regarding microstructure, macrostructure, and Internal State Terms (IST) used by participants with Intellectual Disability. The objective was to examine the effectiveness of narrative therapy in improving narration and comprehension abilities in children with Intellectual disabilities.

Methodology

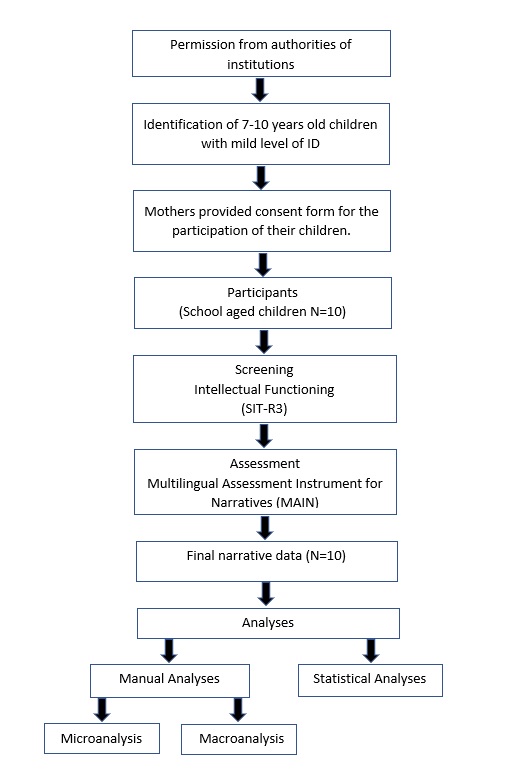

The study used a quantitative, within-subject, pre-post research design to analyze the effectiveness of narrative therapy by comparing participants’ performance before and after the intervention. A purposive sampling technique was applied to collect data from different hospitals and institutions in Lahore. The study hypothesized that there is likely to be an increase in the story structure components of narration abilities of children with Intellectual disabilities and their comprehension abilities. The study included participants whose mental age ranged from four to six years, had mild levels of severity for Intellectual Disability, whose first language was Urdu, and had no prior exposure to narrative therapy. Participants with significant major physical or sensory impairments, with a severe level of intellectual disability, and with neurological or psychological disorders other than intellectual disability were excluded from the participant pool. The study required four months to administer the intervention to ten participants individually, followed by post-intervention follow-up, data interpretation, and analysis. The tool used in the pre- and post-analysis study was the Multilingual Assessment Instrument for Narrative (MAIN). The MAIN (Multilingual Assessment Instrument for Narratives) is a comprehensive tool for evaluating narrative comprehension and production in various languages. It consists of four parallel stories, each carefully constructed with a six-picture sequence based on a multidimensional model of story organization. MAIN offers different elicitation modes, including Model Story, Retelling, and Telling. This enables the comprehensive evaluation of a child’s narrative abilities in diverse linguistic contexts. The instrument’s versatility extends beyond assessment and can be employed for intervention and study purposes. The MAIN provides a valuable and standardized means to evaluate and support narrative development in multilingual populations.20 The Slosson Intelligence Test was used to screen the participants for their mental age. Ethical approval was obtained from Department’s Doctoral Program Committee, Centre for clinial psychology, university of punjab (No: DDPC-001)

The therapy lasted 8 weeks and was 25- 30 minutes long. It was administered three times a week for eight consecutive weeks, totaling 24 sessions (8 weeks × 3 sessions per week = 24). The intervention sessions were conducted in an empty room, and participants received one-to-one sessions in peaceful and airy rooms. The therapist conducted individual therapy sessions. It consisted of three phases. The participants were taught about them, and they had to achieve these levels through various activities undertaken during the study.

The intervention protocol involved building rapport with the participants, pre-assessing them, and introducing them to the three phases of narrative therapy, one at a time, according to the Supporting Knowledge in Language and Literacy (SKILL) intervention protocol. Phase I: Teaching Story Elements. Participants learned about key storytelling elements, including characters, setting, initiating event, internal response, plan, attempt, consequence, and reaction. Each element was represented by an icon and included on a storyboard. The study used wordless picture books designed for the program to illustrate and explain these elements. Stories were narrated, defining each element and providing examples. Participants then created parallel stories with slight variations, using stick figures on storyboards. Once participants could tell their stories independently, the support was gradually removed. Phase II: Connecting and Elaborating Stories, taught linguistic structures and concepts to enhance complex storytelling. The focus was on generating relationships between tale components by utilizing causal language and mental state. Children learned about microstructure elements and incorporated dialogue into their learning. Activities focused on adding complicated events for more intricate narratives. The lessons promoted mental state and causal language to maintain story coherence. Phase III: Creating and editing stories, focused on developing children’s independence in understanding and using narrative structures. It also aimed to enhance metacognitive abilities using a self-scoring rubric for story editing. The rubric targeted macrostructure and microstructure elements, including character count and the use of dialogue. Initially used in conjunction with a specific book, the study was later applied to stories from various prompts.18

The therapy began with the first phase and then proceeded to the subsequent levels after confirming that the participants had a firm grasp and had completed the previous one. Verbal reinforcement was given to the participants to boost their confidence. Audio recordings were carried out to facilitate subsequent analysis. An initial rapport was established with the children through informal conversations before administering the assessment measures. The evaluation process commenced with the appraisal of a fictional tale. A story was presented to the participants through a series of wordless pictures. Participants were instructed to retell the narrative while remaining true to the original details. The analysis encompassed the recording and transcription of the fictional story for further examination. In narrative transcription, mazes (fillers, repetitions, and false starts) and total word tokens were coded according to the MAIN protocol. Manual analysis was conducted on recorded and transcribed stories, focusing on both the microstructural and macrostructural components of narrative. For statistical analysis, since the data was not normally distributed and the assumption of normality was not met, the non-parametric Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test was used in the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software to compare the differences between pre-test and post-test scores within the group.

Figure 1: Illustration of the procedure of the study

Results

The current study’s findings, which examine the effectiveness of narrative therapy in developing narrative proficiency in children with intellectual disabilities, used the Wilcoxon Signed Rank test to compare pre- and post-assessments of story production, including story structure, structural complexity, internal state terms, and the story’s comprehension level. The hypothesis testing revealed statistically significant results, with p-values of 0.005, 0.004, and 0.05 for story structure, complexity, and internal state terms, respectively. The results indicate a substantial effect of narrative therapy on key aspects of story production. The demographic characteristics of participants and study results are reported in the following tables.

Microstructural Analysis: The following Table 4.2 shows that story structure scores were significantly higher after the intervention (Mdn= 15.00, n=10), compared to before (Mdn=2.55, n=10), z= -2.82, p= 0.005, with a large3 effect size, r = 0.63. The test also revealed that structural complexity scores were also significantly higher after the intervention (Mdn= 4.00, n= 10) compared to before (Mdn=7.00, n=10), z= -2.84, p=0.004 with a large effect size, r= 0.63. It was also revealed by the test results that Internal State Terms were significantly higher after the intervention (Mdn= 18.50, n= 10), compared to before (Mdn= 6.00, n= 10). z= -2.89, p= 0.005 with a large effect size, r= 0.63, indicating a large impact of narrative intervention. This means that 40% of the variance in outcomes is attributed to narrative therapy.

Macrostructural analysis: For the pre-assessment, the participants’ narratives had an average of 88.20-word tokens with mazes, with a standard deviation of 7.69. In the post-assessment condition, the average decreased to 70.00-word tokens with mazes, with a slightly increased standard deviation of 9.61. In terms of narratives without mazes, the participants produced an average of 59.20 tokens in the pre-assessment, with a standard deviation of 10.4. However, in the post-assessment, the average significantly increased to 101.70 tokens, with a similar standard deviation of 10.67. The participants demonstrated an average of 5.00 for lemmas in the pre-assessment, with a low standard deviation of 0.94. However, in the post-assessment, the average lemmas increased to 6.9, with a slightly higher standard deviation of 0.99. Regarding communication units, the participants averaged 4.00 in the pre-assessment, with a standard deviation of 0.94. In contrast, the post-assessment showed an increased average of 6.50 communication units, with a standard deviation of 1.17. The results also indicated that narratives tended to become shorter and more lexically diverse, indicating potential developmental changes in narrative abilities.

Story Comprehension:The results also suggested that the narrative therapy intervention had a positive impact on the comprehension abilities of children with intellectual disabilities, resulting in a statistically significant improvement in their skills and ability to understand narrated stories. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test revealed that story comprehension scores were significantly higher after the intervention (Mdn = 6.00, n = 10) compared to before (Mdn = 10.00, n = 10), z = -2.88, p = 0.004, with a large effect size, r = 0.63, indicating a substantial impact of the narrative intervention. This means that 40% of the variance in outcomes is attributed to narrative therapy.

| Table 1: Demographic Characteristics of Sample (N=10) | ||||

| Sample Characteristics | f | % | M | SD |

| Age (in years) | 2.70 | 1.06 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 5 | 50 | ||

| Male | 5 | 50 | ||

| Family Status | ||||

| Joint | 3 | 30 | ||

| Nuclear | 7 | 70 | ||

| Birth Order | ||||

| Firstborn. | 4 | 40 | ||

| Middle child | 4 | 40 | ||

| Last born | 2 | 20 | ||

| M= Mean, S= Standard Deviation, f = Frequency, %= Percentage | ||||

| Table 2: Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test for pre- and post-assessment of Story retelling | ||||||

| Variables | Pre-Assessment | Post-Assessment | ||||

| M | Mdn | M | Mdn | z | p | |

| Story Structure | 3.61 | 2.55 | 14.10 | 15.00 | -2.80 | 0.005** |

| Structural Complexity | 4.20 | 4.00 | 7.00 | 7.00 | -2.84 | 0.004** |

| Internal State Terms | 5.90 | 6.00 | 18.50 | 18.50 | -2.89 | 0.005** |

| M= Mean; Mdn= Median; p= Level of significance <0.05 | ||||||

| Table 3: Mean and standard deviation of the variable narrative length and lexis | ||||

| Variable | Pre-Assessment | Post-Assessment | ||

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| Total no. of word tokens with mazes | 88.20 | 7.69 | 70.00 | 9.61 |

| Total number of tokens without tokens | 59.20 | 10.4 | 101.70 | 10.67 |

| Lemmas | 5.00 | 0.94 | 6.9 | 0.99 |

| Total number of communication units | 4.00 | 0.94 | 6.50 | 1.17 |

| The mean length of communication units | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.01 |

| Note: M= Mean, SD=Standard Deviation | ||||

| Table 4: Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test for pre- and post-assessment of comprehension of story questions. | ||||||

| Variable | Pre-assessment | Post Assessment | ||||

| M | Mdn | M | Mdn | z | p | |

| Comprehension | 5.40 | 6.00 | 9.80 | 10.00 | -2.84 | 0.004** |

| M= Mean; Mdn= Median; p Level of significance <0.05 | ||||||

Discussion

As outlined in the earlier sections, narrative therapy is a therapeutic approach that focuses on shaping individuals’ self-identity and understanding their experiences through storytelling. However, its efficacy in promoting narrative abilities in children with intellectual disabilities remains an area of study. The primary objective of this study was to investigate and evaluate the potential impact of narrative therapy as a therapeutic intervention for enhancing the narrative abilities of children diagnosed with intellectual disabilities.

The first hypothesis of this study proposed that there is likely to be an increase in the story structure abilities of children with Intellectual disability. The results showed that the story structure scores of the children with intellectual disabilities after intervention were higher than before, indicating that narrative therapy successfully improved story structure abilities. These findings are consistent with a study which investigated Teaching Storytelling to a Group of Children with Learning Disabilities: A Look at Treatment Outcomes. The methodology involved teaching elementary school children the proper components of story grammar and syntax. The results indicated that the experimental group participants improved their ability to tell complex stories more than the participants in the control group.21

The study’s second hypothesis postulated that children with intellectual disabilities will likely have improved comprehension abilities. The findings showed that post-intervention comprehension scores were higher than pre-intervention scores, indicating that narrative therapy successfully enhances the comprehension abilities of children with intellectual disabilities. A study investigated comprehension of Students with Significant Intellectual Disabilities and Visual Impairments during Shared Stories. In this study, the listening comprehension of two individuals with Intellectual Disabilities was improved using a least-to-most prompt system. The study’s findings indicated that both individuals provided the correct number of comprehension answers to questions in all three books.22

The findings are also consistent with a study conducted on the effect of narrative Intervention on Storytelling and Personal Story Regeneration Skills in Preschoolers with Risk Factors and Narrative Language Delays. The study investigated the effect of a narrative intervention on the storytelling and personal story-generation skills of preschool-age children with narrative language delays/risk factors. In a small group setting, materials, activities, and support were systematically adapted during sessions to promote gradually more independent oral narration practice. The participants were five preschoolers from a Head Start preschool classroom who scored below average on two narrative language tasks. Participants made substantial gains in narrative retelling, demonstrated improved preintervention to postintervention scores for personal story generation, and maintained these improvements when assessed following a two-week break.23

Conclusion

The findings revealed that the story structure and comprehension scores were significantly higher following the intervention, demonstrating the efficacy of narrative therapy in developing narrative abilities in children with intellectual disabilities. The study’s positive findings showed that participants benefited from this story therapy strategy. The stories in this intervention employed common Urdu vocabulary that is culturally suitable and commonly used in schools in Pakistan. The intervention helped children learn basic story structure, internal state terms, and comprehension.

References

- Westby,C.,& Culatta,B.(2016).Telling tales: Personal event narratives and life stories. Language, Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, 47(4), 260–282.

- Katz-Bernstein, N., & Schröder, A. (2017). Narration – A Task for Speech Therapy and Language Support?! The Dortmund Therapy Concept for Interaction and Narrative Development (DO-TINE). Sprachtherapie aktuell: Forschung – Wissen – Transfer, e2017–e2010.

- Neitzel, I. (2023). Narrative abilities in individuals with Down syndrome: single case profiles. Frontiers in Psychology, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1116567

- Labov, W. (2013). The language of life and death: The transformation of experience in oral narrative. Cambridge University Press.

- Pauls, L. J., & Archibald, L. M. (2021). Cognitive and linguistic effects of narrative- based language intervention in children with Developmental Language Disorder. Autism & Developmental Language Impairments, 6. https://doi.org/10.1177/23969415211015867

- Altman, C., Avraham, I., Meirovich, S. S., & Lifshitz, H. (2022a). How do students with intellectual disabilities tell stories? An investigation of narrative macrostructure and microstructure. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 35(5), 1119–1130.

- McCabe, A., Bliss, L., Barra, G., & Bennett, M. (2008). Comparison of personal versus fictional narratives of children with language impairment. American Journal of Speech- Language Pathology, 17(2), 194–206. https://doi.org/10.1044/1058-0360 (2008/019)

- White, M., & Epston, D. (1990). Narrative means to therapeutic ends. http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA2877320X

- Petersen, D. B., Brown, C. L., Ukrainetz, T. A., Wise, C., Spencer, T. D., & Zebre, J. (2014). Systematic, individualized narrative language intervention on the personal narratives of children with autism. Language Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, 45(1), 67–86. https://doi.org/10.1044/2013_lshss-12-0099

- Gillam, S., Gillam, R., & Reece, K. (2012). Language outcomes of contextualized and decontextualized language intervention: Results of an early efficacy study. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 43(3), 276–291. doi:10.1044/0161 1461(2011/11-0022)

- Rahmani, P. (2011). The efficacy of narrative therapy and storytelling in reducing reading errors of dyslexic children. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 29, 780–785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.11.305

- He, H., Zhu, L., Chan, S. W., Liam, J. L. W., Li, H. C. W., Ko, S. S., Klainin‐Yobas, P., & Wang, W. (2015). Therapeutic play intervention on children’s perioperative anxiety, negative emotional manifestation, and postoperative pain: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 71(5), 1032–1043. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12608

- Altman, C., Avraham, I., Meirovich, S. S., & Lifshitz, H. (2022a). How do students with intellectual disabilities tell stories? An investigation of narrative macrostructure and microstructure. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 35(5), 1119–1130. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12997

- Baldiwala, J., & Kanakia, T. (2021). Using narrative therapy with children experiencing developmental disabilities and their families in India: A qualitative study. Journal of Child Health Care, 26(2), 307. https://doi.org/10.1177/13674935211014739

- Brown, D. A., Brown, E., Lewis, C. N., & Lamb, M. E. (2018). Narrative skill and testimonial accuracy in typically developing children and those with intellectual disabilities. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 32(5), 550–560. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3427

- Pauls, L. J., & Archibald, L. M. (2021). Cognitive and linguistic effects of narrative- based language intervention in children with Developmental Language Disorder. Autism & Developmental Language Impairments, 6. https://doi.org/10.1177/23969415211015867

- Nejatian, H., & Miri, M. (2023). Investigation of Effect of Storytelling on Verbal Language of Autism Children (Mild To Moderate Spectrum). 3rd International Conference on Language and Education, 172–175. https://doi.org/10.24086/iclangedu2023/paper.962

- Gillam, S., Gillam, R., & Laing, C. (2012). Supporting Knowledge in Language and Literacy (SKILL) (Curriculum guide to teaching narratives with DVD, manual, and progress monitoring tools). Logan, UT: Utah State University, Commercial Enterprises.

- MAIN · Multilingual Assessment Instrument for Narratives. (n.d.). MAIN. https://main.leibnizzas.de/

- Gagarina, N., Klop, D., Kunnari, S., Tantele, K., Välimaa, T., Bohnacker, U., & Walters, J. (2019). MAIN: Multilingual Assessment Instrument for Narratives – revised. ZAS Papers in Linguistics, 63, 20. https://doi.org/10.21248/zaspil.63.2019.516

- Klecan-Aker, J. S., Flahive, L., & Fleming, S. (1997). Teaching storytelling to a group of children with learning disabilities: A look at treatment outcomes. Contemporary Issues in Communication Science and Disorders, 24(Spring), 17–26. https://doi.org/10.1044/cicsd_24_s_17

- Mims, P. J., Browder, D. M., Baker, J. N., Lee, A., & Spooner, F. (2009). Increasing Comprehension of Students with Significant Intellectual Disabilities and Visual Impairments during Shared Stories. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 44(3), 409–420.

- Spencer, T. D., & Slocum, T. A. (2010). The Effect of a Narrative Intervention on Story Retelling and Personal Story Generation Skills in Preschoolers with Risk Factors and Narrative Language Delays. Journal of Early Intervention, 32(3), 178–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053815110379124

| Copyright Policy

All Articles are made available under a Creative Commons “Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International” license. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/). Copyrights on any open access article published by Journal Riphah college of Rehabilitation Science (JRCRS) are retained by the author(s). Authors retain the rights of free downloading/unlimited e-print of full text and sharing/disseminating the article without any restriction, by any means; provided the article is correctly cited. JRCRS does not allow commercial use of the articles published. All articles published represent the view of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of JRCRS. |