Original Article: JRCRS. 2025; 13(4):203-209

3- Comparative Effects of Neural Mobilization of Sciatic Nerve Versus Stretching Among Patients with Piriformis Syndrome: A Randomized Clinical Trial

Muhammad Usman1, Rabia Khan2, Syeda Anum Riaz3, Ghousia Shahid4, Sayyeda Tahniat Ali5, Abida Arif6

1 2 4 5 6 Assistant Professor, Bahria University Health Sciences Campus Karachi, Pakistan

3 Consultant Physiotherapist, Neuro Clinic Karachi, Pakistan

Full-Text PDF DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.53389/JRCRS.2025130403

ABSTRACT:

Background: Piriformis syndrome is considered as painful musculoskeletal condition resembling sciatica. It is responsible for 6% of cases of low back pain and is frequently unrecognized in clinical setting.

Objective: To compare the effects of neural mobilization of Sciatic nerve versus stretching of piriformis muscle in patients with piriformis syndrome.

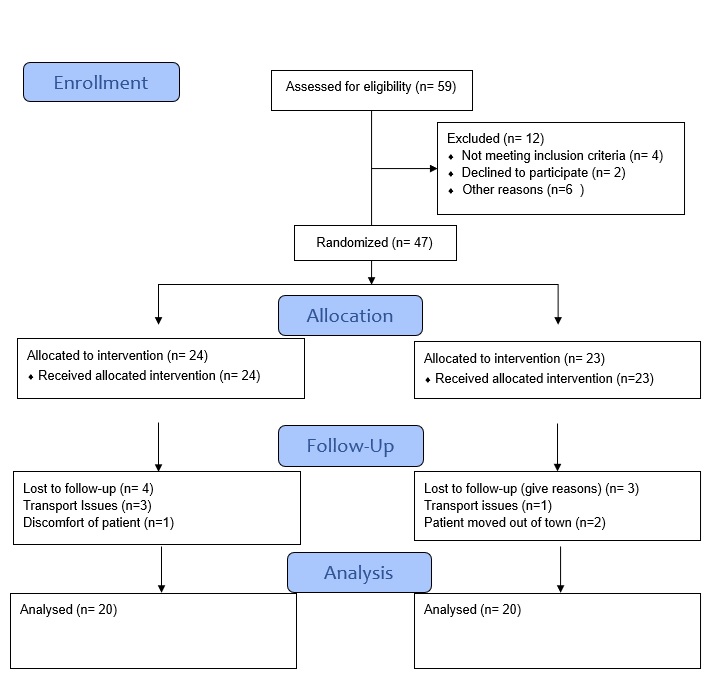

Methodology: All patients coming to Physiotherapy OPD complained about radiating pain in back and legs were screened for sciatica and piriformis syndrome. A total of 40 patients were selected. They were randomly divided into 2 groups; each group contained 20 patients. Group A received neural mobilization of sciatic nerves while Group B received stretching of piriformis muscle. Both groups received treatment for 3 days a week for 2 weeks. Visual analogue Scale (VAS), hip range of motion (ROM) (flexion, abduction and external rotation) and FAIR test were performed pre and post intervention and results were compared for any improvements. SPSS version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for Statistical analyses. Paired t-tests were applied for within-group comparisons, and independent t-tests for between-group comparisons. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) and 95% confidence intervals were also calculated. (Clinical Trial Registry Number: NCT06808659)

Results: The difference in means for all the assessment parameters pre and post treatment showed significant improvement in both groups. Hip flexion ROM, Hip external rotation, Hip abduction ROM, FAIR test, and VAS showed no significant difference when both groups were compared.

Conclusion: This study concluded that both neural mobilization of the sciatic nerve and piriformis stretching significantly improved pain and hip function, but neither technique was superior. These findings suggest that both approaches are effective and may be considered equally viable treatment options for piriformis syndrome.

Keywords: Visual analogue scale, physiotherapy, pain management, Piriformis syndrome, FAIR test, Range of motion.

Introduction:

The name piriformis is derived from two Latin words, Pyrum’ meaning pear and ‘forma’ meaning shape or form: due to its somewhat resemblance to a pear shape. Piriformis muscle is situated in proximity to sciatic nerve; Piriformis (PS) includes pain in the buttocks, hips and lower limbs. Many synonyms are used for this condition in the previous literature, such as ‘deep gluteal syndrome’, pelvic outlet syndrome’ and piriformis syndrome.1 When sciatic nerve is compressed at piriformis muscle’s location it is termed as Piriformis Syndrome.2

In adults presenting with chronic low back or gluteal pain, piriformis syndrome (PS) represents a not-insignificant contributor. A cross-sectional clinical study conducted in Lahore, Pakistan, assessed 224 patients suffering from chronic low back pain and gluteal discomfort. Using a modified FAIR test for diagnosis, the investigators found that 23.7% of participants met the clinical criteria for piriformis syndrome, with 7.6% of these also experiencing sciatica-like symptoms. This clearly indicates that PS should be considered in the differential diagnosis of persistent buttock or back pain.3

Moreover, PS appears to contribute to a considerable proportion of sciatica presentations. In an observational evaluation of 110 patients with sciatica, 66 demonstrated trigger-point tenderness in the piriformis muscle and were administered local muscle injections. Among them, 40.9% reported a ≥ 50% pain reduction, confirming a diagnosis of PFS. These figures highlight that PS may be far more prevalent in sciatica patients than previously appreciated, emphasizing the need for increased clinical awareness.4

Piriformis syndrome is peripheral neuritis which is caused by abnormality of piriformis muscle. Piriformis syndrome can disguise itself as other somatic dysfunctions, such as intervertebral discitis, lumbar Radiculopathy, sacroiliitis, sciatica, trochanteric bursitis. Chronic low back pain comprises of 16% of total or partial work disability. Researchers estimate that 6% of the patients who are diagnosed as having low back pain have piriformis syndrome.5

Description of patient’s pain location is often not precise, pain is generally felt in hip, coccygeal area, buttock, groin and felt down to the posterior or lateral side of the leg. Limping and dragging of the affected leg are also seen. It was discovered by Thiele that pain that radiated down the posterior thigh was due to muscle spasm and hypertrophy which irritated the sciatic nerve.6

Piriformis is a flat pyramidal shaped muscle. Piriformis muscle arises from the pelvic surface of the sacrum, greater sciatic notch, and the Sacro tuberous ligament. The lower attachment is the superior border of greater Trochanter of femur. Piriformis muscle was innervated by Ventral rami of the S1 and S2 spinal nerve. Abduction and external rotation of the hip joint is mainly carried out by piriformis muscle. Below piriformis muscle sciatic nerve, posterior femoral cutaneous nerve, gluteal nerves, and the gluteal vessels passes.7

There are two components that contribute to the clinical manifestation of piriformis syndrome, one is somatic, and the other component is neuropathic. The myofascial pain syndrome of piriformis muscle is the somatic component of piriformis syndrome. Piriformis syndrome presents as myofascial pain due to muscle itself, or nerve compression syndrome.8 Radiculopathy, fatigue, overwork, overload, trauma can result in trigger point activation in skeletal muscle. Activities that usually involve rotation of hips in weight bearing can overload or fatigue the muscle easily. Blunt trauma and car accidents can also result in the activation of trigger points in piriformis muscle. Activation of trigger points may also occur because of prolonged maintenance of a position in which the muscle is shortened.9

The neuropathic component suggests the compression and irritation of sciatic nerve as it courses through the infrapiriform foramen. Irritation and compression contribute to the classical pain pattern. In some reports there is entrapment of sciatic nerve due to a mass lesion near greater sciatic foramen. This mass can be a hypertrophied piriformis muscle or myositis ossificans, hematoma or bursitis of piriformis. Tight piriformis muscle is thought to produce direct pressure on sciatic nerve. Tightness in piriformis can give rise to entrapped sciatic and pudendal nerves. During the stance phase of gait cycle the internal rotation of hip puts excessive stress on piriformis muscle. This repetitive overused causes the muscle to hypertrophy and thus causes the constriction of sciatic nerve. Gait abnormalities altered biomechanics and leg length discrepancies can cause excessive internal rotation of hips leading to stretching and shortening of piriformis muscle.10

Some researchers have also divided piriformis syndrome into two types; primary and secondary. Primary piriformis syndrome is said to occur when there is an anatomic cause present like split or divided sciatic nerve. Secondary piriformis syndrome is said to occur when there is other cause that triggers piriformis syndrome like macro trauma, ischemic mass or simple ischemia. Macro trauma can occur due to direct trauma to buttocks, inflammation of soft tissue, and spasm which results in sciatic nerve compression. Overuse of piriformis muscle such as long-distance walking or running or direct compression such as ‘wallet neuritis’ which is caused by trauma sitting on hard surfaces can causes micro trauma.11

The objective of the study is to compare the effectiveness of neural mobilization of the sciatic nerve versus stretching of the piriformis muscle in patients with piriformis syndrome. Although both interventions are frequently used in clinical practice, there is a lack of high-quality studies directly comparing their effectiveness. Addressing this gap, our study aims to provide evidence to guide physiotherapists in selecting the most appropriate conservative management strategy.

Methodology

It was randomized clinical trial conducted on 40 participants. Sample size was calculated using OpenEpi. We assumed a medium effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.5), a confidence level of 95%, and a power of 80%. Ethical approval was taken from Institutional Ethical Review Committee of Isra Institute of Rehabilitation Sciences, Isra University, Karachi Campus. (Ref no: IERC/IIRS-IU-KC/18/005), the data was collected from June 2024 to December 2024. This yielded a minimum sample of 36 participants, which increased to 40 to account for potential dropouts, divided into two groups. Total duration of the study was six months after the IRB approval. Participants who came to physiotherapy OPD of Rabia Moon Institute of Neuro-sciences Trust with the diagnosis of back pain radiating pain towards legs and having positive lasegue sign, Positive piriformis sign and Tenderness at sciatic notch (over piriformis muscle) were included in the study and patients having Prior surgery of lumbar spine (laminectomy), Unrecognized pelvic fracture, Know case of renal stones, Disc herniation in lumbar spine and Myositis ossificans of piriformis muscle were excluded from the study. SPSS version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for statical analysis. Paired t-tests were applied for within-group comparisons, and independent t-tests for between-group comparisons. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) and 95% confidence intervals were also calculated. Diagnostic criteria were based on a combination of Lasegue, FAIR, and sciatic notch tenderness tests, which have been supported in previous validation studies.

Participants were then divided into two groups; each group contained 20 patients. The groups were named Group A and Group B. Group A received Neural mobilization while Group B received piriformis Stretching exercises. A trained qualified experienced physiotherapist gives interventions to each group. Frequency of stretching and neural Mobilization was thrice a week for two weeks VAS, hip ROM (flexion, abduction and external rotation) and FAIR test were performed pre and post intervention and results were compared for any improvements. Participants were randomized using computer-generated random numbers with allocation concealed in sealed opaque envelopes. Outcome assessors were blinded to group allocation.

For measuring hip flexion ROM, the inclinometer was attached to a flat rigid surface. Before each measurement the inclinometer was zeroed on a horizontal surface. Participants were asked to lie supine with the knee in flexion; the researcher flexed the hip with one hand to the point where firm end feel was felt or at which pain restricted further movement. Next the researcher aligned the inclinometer parallel to the lateral surface distal femur and reading was noted.

For measuring hip external rotation ROM, the patient was positioned in a prone position. The researcher flexed one knee to 90 degrees and then instructed them to relax; passively rotating the shank towards midline until end feel was felt. The inclinometer was placed lately at distal third of shaft of fibula and reading was noted.

For measuring hip abduction, the extremity to be measured was held in 90-degree hip flexion, with the contralateral leg stabilized at maximum hip extension by an assistant. Then passive hip abduction was performed with the inclinometer placed at the lateral surface of distal third of thigh and reading was noted.

Group A received neural mobilization of sciatic nerve. Neural mobilization was performed with participants in supine position then the therapist griped the test leg from ankle and performed passive hip flexion, the other hand was placed over knee in-order to keep it straight. Then hip adduction, hip medial rotation was added. Neural mobilization was given for approximately 12-15 minutes per session including 30 sec hold and 1-minute rest in between.

Group B received stretching of piriformis muscle while the participants were performed in contralateral decubitus position with affected leg in flexion, adduction and internally rotated position. Manual pressure was applied to the inferior border of muscle, carefully pressing downward pressure tangentially towards the ipsilateral shoulder. Stretch was held for 30 seconds; 3 sets of 10 repetitions were performed with 30 seconds rest in between. 10 to 14 minutes/ of stretching were performed per session.

Figure 1: CONSORT Diagram

Results

The total number of participants was 40. The mean age was found to be 46.25 years (SD 12.833). The minimum age was 22 years, and maximum age was found to be 65 years. The total number of male patients was 29 (72.5%), female patients were 11(27.5%). The average body mass index (BMI) of participants was 26.4 ± 3.2 kg/m², indicating that most individuals were within the overweight range. Regarding occupational background, 24 participants (60%) were engaged in sedentary professions, while 16 (40%) performed manual or physically demanding work. The mean duration of symptoms was 7.2 ± 3.5 months, reflecting a moderately chronic presentation of piriformis syndrome among participants. Symptoms showed that the right side was affected in 22 participants (55%) and the left side in 18 participants (45%). Common comorbidities included diabetes mellitus in 8 participants (20%) and hypertension in 10 participants (25%) (Table 1).

Within-Group Comparisons: Paired t-test analyses were performed to determine changes within each group before and after intervention (Table 2). In Group A (Neural Mobilization), there was a statistically significant reduction in pain intensity measured by the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), decreasing from 9.25 ± 1.02 to 2.80 ± 1.99 (p < 0.001). Significant improvements were also observed in hip flexion ROM (65.00 ± 22.06° to 97.25 ± 11.75°, p < 0.001), abduction ROM (31.25 ± 12.23° to 41.50 ± 13.48°, p < 0.001), and external rotation ROM (28.50 ± 10.27° to 38.10 ± 10.76°, p < 0.001).

In Group B (Piriformis Stretching), a similar pattern of improvement was observed. VAS scores reduced significantly from 9.15 ± 1.09 to 3.05 ± 1.43 (p < 0.001). Hip flexion ROM improved from 79.25 ± 18.94° to 96.35 ± 13.85° (p < 0.001), abduction ROM from 30.00 ± 9.67° to 34.55 ± 7.61° (p = 0.018), and external rotation ROM from 29.25 ± 9.22° to 33.45 ± 7.16° (p = 0.039).

These findings indicate that both neural mobilization and piriformis stretching produced significant within-group improvements in pain and hip joint mobility.

Chi-square test was used to assess categorical changes in FAIR test outcomes. Both neural mobilization and piriformis stretching groups showed statistically significant improvements in pain and hip joint mobility (p < 0.05). However, the reduction in positive FAIR test cases was not statistically significant in either group (p > 0.05) (Table 3).

Between-Group Comparisons: Independent t-test analyses were performed to compare post-treatment outcomes between Group A and Group B (Table 4).

The mean post-intervention VAS score was 2.80 ± 1.99 in Group A and 3.05 ± 1.43 in Group B (p = 0.601), indicating no statistically significant difference between the two interventions. Similarly, no significant between-group differences were observed in hip flexion (97.25 ± 11.75° vs. 96.35 ± 13.85°, p = 0.796), abduction (41.50 ± 13.48° vs. 34.55 ± 7.61°, p = 0.070), or external rotation (38.10 ± 10.76° vs. 33.45 ± 7.16°, p = 0.109).

Chi-square test was used to compare categorical FAIR test results. No statistically significant differences were observed between the two groups in any outcome measure (p > 0.05), indicating comparable treatment effectiveness (Table 5).

| Table 1: Demographics distribution of Participants | |

| Variable | Value |

| Total Participants (n) | 40 |

| Mean Age (years) | 46.25 |

| Standard Deviation (Age) | 12.83 |

| Minimum Age (years) | 22 |

| Maximum Age (years) | 65 |

| Male (n, %) | 29 (72.5%) |

| Female (n, %) | 11 (27.5%) |

| Mean Body Mass Index (BMI, kg/m²) | 26.4 |

| SD (BMI) | 3.2 |

| Occupation – Sedentary (n, %) | 24 (60%) |

| Occupation – Manual Worker (n, %) | 16 (40%) |

| Duration of Symptoms (months, Mean ± SD) | 7.2 ± 3.5 |

| Side Affected (Right/Left, n, %) | 22 (55%) Right, 18 (45%) Left |

| Comorbidities (Diabetes/Hypertension, n, %) | 8 (20%) Diabetes, 10 (25%) Hypertension |

| Table 2: Paired t-test Results for Within-Group Comparisons | |||||

| Outcome Measure | Group | Pre-treatment Mean ± SD | Post-treatment Mean ± SD | Mean Difference | p-value |

| VAS (pain) | A – Neural Mobilization | 9.25 ± 1.02 | 2.80 ± 1.99 | 6.45 | <0.001 |

| B – Piriformis Stretch | 9.15 ± 1.09 | 3.05 ± 1.43 | 6.10 | <0.001 | |

| Hip Flexion (°) | A | 65.00 ± 22.06 | 97.25 ± 11.75 | 32.25 | <0.001 |

| B | 79.25 ± 18.94 | 96.35 ± 13.85 | 17.10 | <0.001 | |

| Hip Abduction (°) | A | 31.25 ± 12.23 | 41.50 ± 13.48 | 10.25 | <0.001 |

| B | 30.00 ± 9.67 | 34.55 ± 7.61 | 4.55 | 0.018 | |

| External Rotation (°) | A | 28.50 ± 10.27 | 38.10 ± 10.76 | 9.60 | <0.001 |

| B | 29.25 ± 9.22 | 33.45 ± 7.16 | 4.20 | 0.039 | |

| Table 3: Chi-square Test Results for Within-Group Comparisons | |||||

| Outcome | Group | Pre (n=positive) | Post (n=positive) | Test | p-value |

| FAIR Test | A | 14 | 4 | χ² = 1.61 | 0.207 |

| FAIR Test | B | 19 | 14 | χ² = 1.07 | 0.300 |

| Table 4: Independent t-test Results for Between-Group Post-Intervention Comparison | ||||

| Outcome Measure | Group A (Neural Mobilization) Mean ± SD | Group B (Piriformis Stretch) Mean ± SD | Mean Difference | p-value |

| VAS (post) | 2.80 ± 1.99 | 3.05 ± 1.43 | 0.25 | 0.601 |

| Hip Flexion (°) | 97.25 ± 11.75 | 96.35 ± 13.85 | 0.90 | 0.796 |

| Hip Abduction (°) | 41.50 ± 13.48 | 34.55 ± 7.61 | 6.95 | 0.070 |

| External Rotation (°) | 38.10 ± 10.76 | 33.45 ± 7.16 | 4.65 | 0.109 |

| Table 5: Independent t-test and Chi-square Test Results for Between-Group Post-Intervention Comparisons | ||||

| Outcome Measure | Group A (Neural Mobilization) n (%) Positive | Group B (Piriformis Stretch) n (%) Positive | Statistical Test | p-value |

| FAIR Test (post) | 4 (20%) | 14 (70%) | χ² = 0.657 | 0.657 |

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to determine the comparative effects of neural mobilization of sciatic nerve versus stretching of piriformis muscle in patients with piriformis syndrome. Piriformis syndrome has been explained to occur due to piriformis muscle with or without sciatic nerve. The three cardinal symptoms that commonly occur in piriformis syndrome are buttock pain, radiating pain to posterior thighs and pain that aggravates from prolonged sitting or position changes.

The current study compared neural mobilization of sciatic nerve and piriformis stretching effectiveness in piriformis syndrome. The subjects were divided into two groups; one group received neural mobilization and the other received piriformis stretching. Hip flexion ROM, hip abduction ROM, hip external rotation ROM, VAS, and FAIR tests were measured before and after intervention. Two weeks of intervention showed that both groups had significantly improved hip ROM, VAS and FAIR tests. Although all the assessment parameters except FAIR test showed significant improvement but the difference between both treatments was not statistically significant. So, the study cannot conclude which treatment is better than the other treatment.

Effect of neural mobilization in the form of slump stretching in patients with non-radicular low back pain was investigated by Ridehalgh et al (2025) shows significant improvement in pain by using FAIR test.12 Our study also showed improvement in FAIR test after intervention in both piriformis stretch group as well as neural mobilization group. The study acknowledged that the FAIR test has limited diagnostic reliability, and this limitation is highlighted in the discussion.

Research performed by Chaudhary et al (2021) showed improvement in the group that underwent stretching along with neural mobilization as compared to stretching alone in patients with piriformis syndrome.13 Our research has shown improvement in the stretching group, but statistically significant differences were not noticed.

It has been explained by Khakneshin et al (2021) that piriformis is an external rotator and abductor of hip and functions as synergist with quadrates femoris, obturator internus and obturator externus and gamellus superior and inferior. Previous authors addressed hip abductor weakness, and they noted that hip abductor strengthening “seemed to hasten recovery.14 Current research has also shown significant improvement in hip abduction ROM in both groups. However, the difference between both groups showed no significant difference.

A critical limitation of present study was the relatively small sample size, which may have affected the statistical power and the generalizability of the results. Additionally, the research was conducted within a single hospital setting, which may not represent broader populations or clinical practices in different regions. Another constraint was the demographic characteristics of the participants; most were illiterate or unable to understand English, which could have influenced their comprehension of instructions and potentially impacted the accuracy of the data collected. Another important limitation is the relatively short 2-week intervention period, which restricts conclusions about long-term effects. Future studies should consider extended follow-up.

For future research, it is recommended that studies be conducted on larger and more diverse populations to obtain results that are more robust and widely applicable. Furthermore, it would be beneficial to compare various stretching techniques for the piriformis muscle in order to evaluate and determine which methods yield the most effective clinical outcomes. Another limitation of this study is the unequal gender distribution, with a higher proportion of male participants compared to females. This imbalance may restrict the generalizability of the findings to the wider population, particularly female patients with piriformis syndrome. Future studies should aim to include a more balanced sample to enhance external validity.

Conclusion

This study concluded that both neural mobilization of the sciatic nerve and piriformis stretching significantly improved pain and hip function, but neither technique was superior. These findings suggest that both approaches are effective and may be considered equally viable treatment options for piriformis syndrome. This study concluded that there is no significant difference between neural mobilization of the sciatic nerve and piriformis stretching in treating piriformis syndrome. Both interventions significantly improved pain (VAS) and hip ROM (flexion, external rotation, and abduction), but neither proved superior. FAIR test results also showed no notable difference. Thus, the study supports the null hypothesis, indicating both treatments are equally effective in managing piriformis syndrome.

References

- Siraj SA and Dadgal R. Physiotherapy for piriformis syndrome using sciatic nerve mobilization and piriformis release. Cureus 2022; 14.

- Adiyatma H and Kurniawan SN. Piriformis syndrome. Journal of Pain, Headache and Vertigo 2022; 3: 23-28.

- Batool N, Azam N, Moafa HN, et al. Prevalence of piriformis syndrome and its associated risk factors among university students in Pakistan: a cross-sectional study. BMJ open 2025; 15: e092383.

- Yürük D, Can E, Genç Perdecioglu GR, et al. Prevalence of priformis syndrome in sciatica patients: Predictability of specific tests and radiological findings for diagnosis. British Journal of Pain 2024; 18: 418-424.

- Son B-c and Lee C. Piriformis syndrome (sciatic nerve entrapment) associated with type C sciatic nerve variation: a report of two cases and literature review. Korean Journal of Neurotrauma 2022; 18: 434.

- Guizzi A, Saccomanno MF, Carapella N, et al. Piriformis: Muscle Injury, Syndrome, Sciatic Nerve. Orthopaedic Sports Medicine: An Encyclopedic Review of Diagnosis, Prevention, and Management. Springer, 2025, pp.1-13.

- Chang C, Jeno SH and Varacallo MA. Anatomy, bony pelvis and lower limb: piriformis muscle. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing, 2023.

- Siahaan YMT, Tiffani P and Tanasia A. Ultrasound-guided measurement of piriformis muscle thickness to diagnose piriformis syndrome. Frontiers in neurology 2021; 12: 721966.

- Zhai T, Jiang F, Chen Y, et al. Advancing musculoskeletal diagnosis and therapy: a comprehensive review of trigger point theory and muscle pain patterns. Frontiers in Medicine 2024; 11: 1433070.

- Abu Bakar Siddiq M, Jahan I and Rasker JJ. Piriformis Syndrome: Epidemiology, Clinical features, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Piriformis Syndrome. Springer, 2023, pp.75-87.

- Iyer KM. Hip Joint: Modified Posterior Approach. The Hip Joint. Jenny Stanford Publishing, 2023, pp.1-46.

- Ridehalgh C and Ward J. Management of nerve related musculoskeletal pain. Petty’s principles of musculoskeletal treatment and management: a handbook for therapists Amsterdam: Elsevier 2023: 179-196.

- Chaudhary S, Sheikh M, Chaudhary NI, et al. Effect of neural tissue mobilization in combination with ultrasonic therapy verses ultrasonic therapy in deep gluteal syndrome-a comparative study. 2021.

- Khakneshin A, Javaherian M and Attarbashi Moghadam B. The efficacy of physiotherapy interventions for recovery of patients suffering from piriformis syndrome: a literature review. Journal of Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences 2021; 19: 1304-1318.

| Copyright Policy

All Articles are made available under a Creative Commons “Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International” license. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/). Copyrights on any open access article published by Journal Riphah college of Rehabilitation Science (JRCRS) are retained by the author(s). Authors retain the rights of free downloading/unlimited e-print of full text and sharing/disseminating the article without any restriction, by any means; provided the article is correctly cited. JRCRS does not allow commercial use of the articles published. All articles published represent the view of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of JRCRS. |