Systematic Review: JRCRS. 2025; 13(4):193-202

2- Synchronization of Exercise Timings Relative to Glycemic Control – A Systematic Review

Sheeza Ayub1, Sausan Fatima2, Anwar Zaib3, Muhammad Faisal Qureshi4

1 Physiotherapist, NeuroGym DHA, Karachi, Pakistan

2 3 Physiotherapist, Liaquat National Hospital, Karachi, Pakistan

4 Senior Lecturer / Physiotherapist, Taqwa Institute of Physiotherapy, Karachi, Pakistan

Full-Text PDF DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.53389/JRCRS.2025130402

ABSTRACT:

Background: Diabetes mellitus is a chronic metabolic disorder characterized by impaired glucose regulation. Exercise is a key non-pharmacological strategy to improve insulin sensitivity and metabolic control. Emerging evidence indicates that the timing of exercise, especially in the afternoon, may optimize glycemic outcomes.

Objective: To analyze the effect of exercise timing on glycemic markers in individuals with metabolic diseases like diabetes.

Methodology: For this review, two authors performed literature searches in numerous databases. For quality assessment Modified Downs and Black Checklist has been used. After a comprehensive analysis, seven studies met the inclusion criteria.

Results: Afternoon timing results had favorable outcomes, showing a decline in their glucose parameters. Unlike morning timing also showed considerable results in a decrease of glycemic factors. Studies reported statistically significant findings in favor of afternoon exercise. For example, Savikj et al. (2018) reported reduced blood glucose levels based on CGM in the afternoon group (6.1 ± 0.4 mmol/l) compared to the morning group (6.6 ± 0.4 mmol/l; p < 0.05). Mancilla et al. (2020) showed a decline in fasting plasma glucose in the afternoon group (−0.3 ± 1.0 mmol/l) versus an increase in the morning group (+0.5 ± 0.8 mmol/l), with a significant intergroup difference (p = 0.02). VO₂ max improvements were significant in both groups with p-values of 0.003 (morning) and 0.001 (afternoon). Additionally, Gomez et al. (2015) found that hypoglycemic events were significantly lower following morning exercise sessions compared to afternoon (p < 0.0001).

Conclusion: Afternoon timing plays a pivotal role in reducing the glycemic parameters. Future research endeavors should focus on incorporating larger sample sizes, and more randomized control trials should be conducted on the female population

Keywords: Circadian Rhythm; Diabetes; Exercise Timing; Muscle Clocks; Morning Exercise; Afternoon Exercise

Introduction:

As the world is moving towards modernization and technological advances day by day, it results in the prevailing modern lifestyle characterized by access to energy-dense food, decreased physical activity, irregular sleeping patterns, prolonged sitting, and poor eating habits 1 The above-mentioned habits, which have become a new social norm, have severely impacted the internal physiology and circadian rhythm which leading to a plethora of metabolic diseases.1

Metabolic diseases like diabetes are progressively increasing all around the world; almost half a million people are affected by diabetes worldwide.2 This increasing number of metabolic diseases is becoming a social and economic burden, due to which the prevention of such diseases is emphasized.3 It has been reported that dietary control and regular exercise are considered the best approaches to prevent non-communicable diseases.1 These two strategies are considered the socially acceptable and effective way to reduce the incidence of the development of metabolic disease.1

Apart from time-restricted eating, exercise intervention is an optimal strategy that can delay the onset of 40 chronic metabolic diseases.1 Many cross-sectional studies identify statistical associations between physical activity and insulin sensitivity, even some cases report the complete reversal of insulin resistance.4, 5 The exercise exhibits both acute and chronic improvements in the sensitivity of insulin-related markers. The acute responses, during and after the exercise, were shown as the rapid uptake of glucose into the skeletal muscle.4 These acute responses are evident for up to 72 hours, while the chronic responses produce long-term effects on insulin sensitivity.4

Undoubtedly, exercise has magnificent results on the overall health of human beings but to get specific results, there is a need to target specific factors associated with the exercise to get specific results. The manipulation of exercise mode, exercise intensity, and exercise timing for the optimization of potential benefits is a concern that recent literature is reflecting upon. The associations of the aforementioned factors with diurnal rhythm have become an interesting query for many researchers, and lately, many findings have also been documented. Concerning metabolic diseases, especially diabetes and its relation to circadian rhythm, has been studied extensively by different authors. They also concluded that the disruptions of diurnal rhythms have deleterious effects on metabolic health.6-8 These perturbations mainly occur due to the irregular, conflicting interactions between the environmental factors and the circadian rhythm.9

The central clock located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus SCN of the hypothalamus mainly regulates the circadian rhythm and is considered the only governing pacemaker back in the days.10 Surprisingly, it was found that there are more autonomous pacemakers in the tissues (muscle, bone, cartilage, liver) which are independent of the central clock. Zylka et al (1998 first proposed the idea of oscillating transcripts other than the central clock, which reside outside of the brain.11 These internal clocks are regulated through the photic and non-photic cues that they get from the environment.12 The central and peripheral clocks crave the consistency of these cues to regulate themselves.9 As skeletal muscles are considered an endocrine organ for glucose uptake and homeostasis, the muscle clocks regulate the glycemic control through photic cues of light and dark cycles.13, 14 Therefore, the timing of exercise as a cue has become a matter of concern for glycemic control. The synchronization of exercise timing with the cellular response of muscle exhibits great potency as a therapeutic tool for the management of diabetes,8 but unfortunately, the data in this area is sparse.

Other than glycemic control, the exercise timing exhibits different responses, for example, in the late afternoon, an increment in strength, power, and endurance has been reported than in the early morning.15, 16 In literature, the exercise timings are described in various ways. Some researchers focused on exercise timings relative to meal intake17 and some researchers emphasized at which part of the day (morning or afternoon) a diabetic patient performs the exercise, which is consistent with the objective of our review. The part of the day (in which exercise is performed) should be chosen wisely, as morning and afternoon timings have different effects on the metabolic processes. A recent cross-sectional study18 showed improvement in glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) when moderate to vigorous exercise is performed in the afternoon. Another cross-sectional study showed a 25% reduction in insulin resistance when afternoon exercises were performed by obese middle-aged adults19 Morning exercises compared with afternoon exercise result in an increased oxidative capacity and efficient utilization of glucose substrates.7 The scientific evidence supports the relationship between glucose tolerance and circadian rhythm. The circadian clock, along with exercise performed at a specific time, induces great effects on glucose metabolism.20 Therefore, this systematic review aims to consolidate the existing literature on the effect of exercise timing on glycemic control. This review aims to systematically examine randomized controlled trials that investigate the timing of exercise interventions and their impact on glycemic control.

Methodology:

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines have been followed in this systematic review.21 This systematic review was not registered in PROSPERO or any other database. According to the PRISMA guidelines search strategy, selection, data collection, and risk of bias assessment were conducted and stated in this review. Two authors performed literature searches in the following databases: i) PUBMED/MEDLINE, ii) COCHRANE, iii) EMBASE, iv) OVID, v) SCOPUS, vi) Pedro, vii) CINAHL, viii) TRIP database ix) SPORT Discus from April 2023 to June 2023. The search terms were used, such as “circadian rhythm”, “muscle clocks”, “morning exercise”, “afternoon exercise”, “type 2 diabetes, “glycemic control”, and “exercise timing”. The filters were applied for the year of publication, i.e., 2013-2023, and the type of study, i.e. randomized controlled trial. Studies from the references of included RCTs were also examined.

All the studies in this review were included with the following inclusion criteria: RCTs should be published in the English language, RCTs should be conducted on humans only, the effect of exercise timings should be discussed in the studies, the studies which are conducted within the last decade, i.e. 2013-2023. And the studies with the following exclusion criteria have been removed from this review: The studies in other languages, like Persian, Spanish, German, etc. The studies that only discussed the effect of time-restricted eating on glycemic control. The studies that have discussed the effect of exercise timings only on muscle protein breakdown, strength, and performance.

Two authors independently analyzed the studies according to the inclusion criteria. Before screening, studies were examined thoroughly, and duplicates were removed. The retrieved studies were screened on the basis of titles and abstracts, and then based on full-text articles. The third author reviewed the process of study selection and resolved the disagreements. Two authors independently carried out the extraction of the characteristics from the selected studies. (Refer to Table 1). This review only focuses on the descriptive and qualitative synthesis of the selected studies. A small number of studies were retrieved in this review, and heterogeneity was found in the endpoints, due to which Meta-analysis was not conducted.

The methodological quality of included studies was assessed through the Modified Downs and Black checklist (2016) 22. A 27-item checklist classifies the studies as excellent quality (26-28 points), good quality (20-25 points), fair quality (15-19), and poor quality (< 11 points). (Refer to Table 2). Four authors performed the quality assessment of the studies with discussions and agreement to resolve any observed differences.

Results:

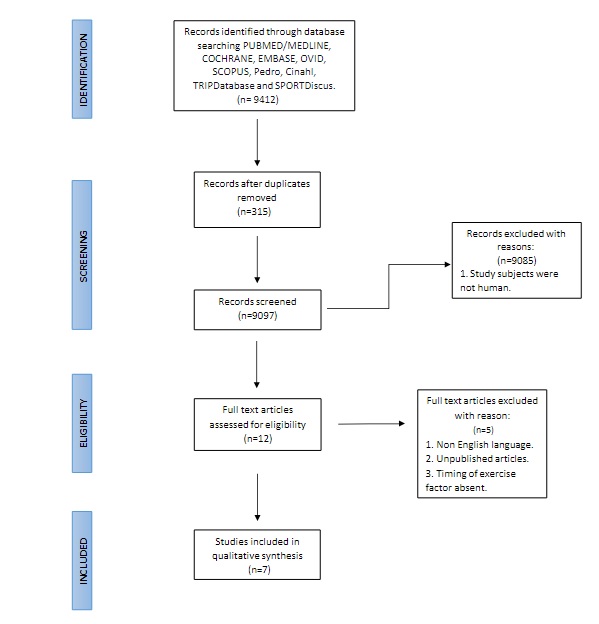

The process of study selection is discussed in the PRISMA flowchart (Figure 1). From different databases and other sources, 9412 research articles were retrieved. After removing the duplicates, 9097 articles were screened with titles and abstracts. The articles that discussed the circadian rhythm and the exercise timings were further reviewed by reading full-text articles. From this analysis, seven randomized control trials were included in the review for qualitative assessment.

Figure 1. PRISMA Flowchart

Seven studies were included in the review, based on the inclusion criteria. These studies 8, 23-28 included adults with diabetes 8, 26-28, sedentary lifestyle and overweight 23, 24, and night shift workers 25. For interventions, exercise programs were followed. High-intensity interval training were performed as an intervention in four studies 8, 23, 25, 28, moderate intensity exercise in two studies 23, 24, aerobic 26, 27, and resistance exercise 26 Some RCTs performed two exercise regimens like high-intensity interval training and moderate intensity interval training were performed as an intervention in one study 23, and resistance and aerobic exercise both were performed in one study.26 The characteristics of included studies are summarized in Table 1.

(CGM-Continuous glucose monitor, TSH-Thyroid-stimulating hormone, PTH- Parathyroid hormone, HFD- high fat diet, HIIT- high intensity interval training. PPG- Postprandial glucose, PPI- Postprandial insulin, OGTT- Oral glucose tolerance testing, REx- resistance exercise, AEx- aerobic exercise, FPG- fasting plasma glucose, ET- exercise training)

The majority of the studies (24-28) are of fair quality 22, and only 2 studies 8, 23 are classified as the good quality according to the Modified Down and Black Checklist (2026). Some studies did not provide sufficient information about the blinding of the subjects 8, 23, 25, 26 and the assessor 8, 25-28 who will measure the outcome? All the studies provide the number of participants, inclusion, and exclusion criteria. The information regarding the participant lost to follow-up is only discussed in three studies.8, 23, 27

(In this checklist, reporting items are discussed in items 1-10, while external validity is discussed in items 11-13, internal validity in items 14-26, and statistical power in item 27). A 27-item checklist classifies the studies as excellent quality (26-28 points), good quality (20-25 points), fair quality (15-19), and poor quality (< 11 points).

In this review, the main objective is to analyze the effect of the timing of exercise on the glycemic markers. All the studies included in this review have documented the effect of exercise timing on different parameters such as insulin levels, fasting plasma glucose levels, HbA1c, etc. Studies 8, 23, 26 suggested that afternoon or evening exercises have a positive impact on glycemic control as compared to morning exercises. These trials demonstrated lower mean interstitial glucose levels and improved insulin sensitivity when physical activity was performed later in the day.

This difference can be attributed to physiological and circadian mechanisms. Afternoon exercise coincides with higher body temperature, enhanced muscle enzyme activity, and improved glucose uptake. Moreover, lower morning insulin sensitivity and higher cortisol levels may limit early-day glucose control, whereas evening sessions optimize metabolic responses and energy utilization.

Savikj et al. (2018) concluded that the High-intensity interval training performed in the afternoon, resulted in reduced glucose concentration based on continuous glucose monitoring (6.2 ± 0.3 and 6.1 ± 0.4 mmol/l for weeks 1 and 2, respectively) when compared to pre-training readings and morning group (6.9 ± 0.4 mmol/l; and 6.6 ± 0.4 mmol/l for week 1 and week 2 respectively) (Table 3) 8 The authors attributed these effects not merely to exercise itself, but to the interaction between exercise timing and metabolic circadian rhythms. Specifically, insulin sensitivity, skeletal-muscle glucose transporter (GLUT-4) expression, and mitochondrial oxidative capacity peak later in the day, enhancing glucose disposal efficiency. The study controlled for exercise intensity and duration between the two groups, thereby isolating time-of-day as the principal differentiating factor influencing glycemic outcomes.

Another RCT 23, which was only conducted on adult men (age 30-45), also suggested that the blood glucose decreases with a great magnitude in the group that performed exercise in the afternoon when compared with the morning group. Mancilla et al. (2020) also suggested that peripheral insulin sensitivity significantly improves (0.03) in the evening group as a result of three sessions of aerobic and resistance exercise. The afternoon group also shows a decline in the fasting plasma glucose (−0.3 ± 1.0 mmol/l) when compared to the morning group (+0.5 ± 0.8 mmol/l), showing a significant intergroup difference with the p-value of 0.02.26 Another parameter named fructosamine (a short-term nonspecific glycation marker which complements HbA1c) has been assessed post-exercise in the morning and afternoon groups 24 Teo et al. (2019) suggested that the Fructosamine showed significant improvement (p-value < 0.01) as a result of exercise training, but there is no significant intergroup difference between the morning and afternoon groups.24

However, some included randomized control trials concluded that overall exercise training has a marked effect on insulin sensitivity in both individuals (with and without type 2 diabetes). Still, there is no statistical improvement when allocated to the morning and afternoon groups 24 In this same study, parameters like post-prandial glucose and post-prandial insulin are affected with respect to time (PPG has improved response in the afternoon group) in type 2 diabetic patients, while the morning exercise cohort has greater effects on the main glycemic markers like HbA1c, fasting glucose, and fructosamine. Similarly, Hannemann et al. (2020) report no significant findings of exercise on HOMA-IR (assess for insulin sensitivity), HBA1c, etc., but this trial only involved the night shift workers.25 M. Savikj et al. (2022) mainly focused on the influence of exercise timing on the tissue metabolome and proteome profile. This study 28 provides insufficient knowledge about the glycemic markers, except that the fasting insulin levels differed during sampling occasions (morning and afternoon), but comparisons were not significant.

Studies 23-26 included in this review, also analyze the effect of exercise timings on VO2 max and peak power output. Exercise training increases VO2 max and PPO, and significant results of VO2max have been reported with the p-value of 0.003 and 0.001 in the morning and afternoon groups, respectively.23 These findings were consistent with the findings of Teo et al (2019).24 In the night shift workers, VO2 max, maximal workload, and maximal heart rate did not significantly improve after exercise intervention.25

However, the afternoon group showed improvement in the maximal power output (+36.6 ± 22 vs. +24.4 ± 11.3 Watt in afternoon vs. morning, p = 0.08), and VO2 max (+3.0 ± 2.1 vs. +1.8 ± 2.2 ml kg-1 min-1 in afternoon vs. morning, p = 0.1) (Table 3) but did not reach the statistical significance.26

The timing of exercise affects the parathyroid hormone and thyroid-stimulating hormone when compared to the pre-training.8 Afternoon exercise increases the PTH and TSH levels and reduces T4 concentration. Morning HIIT also affects the TSH levels, while PTH and T4 remain unaltered as compared to the pre-training levels.

The group that performed exercise in the evening also regulates the metabolites involved in lipid and amino acid metabolism. Exercises performed in the evening resulted in significant intergroup differences compared with the control group. They detected changes in 56 metabolites from the morning sample and nine metabolites from the evening sample.23

Savikj et al. (2022) extensively discussed the effect of morning and afternoon exercise on different proteomes and metabolomes. In this study morning exercise group and the afternoon exercise group performed HIIT for two weeks. According to this study 28 morning training increases plasma lipids and plasma carbohydrates, along with the skeletal muscle cofactors and vitamins, except that the skeletal muscle lipids were lowered compared to the afternoon group. Afternoon HIIT increases adipose tissue lipids and reduces plasma cofactors and vitamins.28

Type-2 diabetic patients were the majorly focus of the included studies, but hypoglycemic events after morning and afternoon exercise were also reported by Gomez et al.27 It was concluded that the events of hypoglycemia were significantly lower after the morning exercise sessions versus the afternoon exercise sessions (p-value <0.0001) in type 1 diabetic patients.

In summary, the effect of exercise and the timing of exercise on diabetes was assessed through different methods in the included studies. The heterogeneity in the results of the included studies that have been reviewed above. The timing of exercise is an area ripe for research, but the studies included in the review have supported the hypothesis that the exercise timings have a crucial effect on glycemic control.

| Table 1: Characteristics of Recruited Studies | ||||||

| Study | Sample demographics | Training duration | Exercise program | Exercise timing | Endpoints | Main outcomes |

| Gomez et al. (2015)(27) | 32 subjects | 2 days | 60 minutes of moderate aerobic workout | morning (07:00) afternoon (04:00) |

CGM | A significant difference was found in the CGM morning time. |

| Age: 30.31 ±

12.66 years old |

||||||

| Gender: male | ||||||

| BMI:23.3 ± 3.4

kg/m2 |

||||||

| HbA1c: 7.28 ±

1.03 % |

||||||

| Savikj et al. (2018) (8) | 11 subjects | 2 weeks; 3 times per week | 2 sets of 6 repetitions HIIT |

morning (08:00) afternoon (16:00) |

Continuous glucose monitor | A statistical difference was found in reduced CGM in the afternoon. |

| Age:60 ± 2

years old |

||||||

| Gender: male | ||||||

| BMI: 27.5 ± 0.6

kg/m2 |

||||||

| HbA1c: NA | ||||||

| Teo et al. (2019)(24) | 40 subjects | 12 weeks; 3 times per week | 3 sets of 12–18 repetitions Moderate intensity exercise |

morning 08:00-10:00 evening 17:00–19:00 |

PPI, PPG, Fructosamine | Marked improvements seen in PPI and PPG, Fructosamine morning time. |

| Age:18-65 years

old |

||||||

| Gender: female

& male |

||||||

| BMI: ≥ 27

kg·m−2 |

||||||

| HbA1c: NA | ||||||

| Hannemann et al. (2020)(25) | 24 subjects | 12 weeks; 1 time per week | 35 minutes HIIT | 2 hours before the night shift worker | VO2max, OGTT | No statistically significant difference was seen. |

| Age:35.7 ± 11.8

years old |

||||||

| BMI:27.8 ± 6.9 kg·m−2 | ||||||

| HbA1c: 5.2 ± 0.6 % | ||||||

| Mancilla et al. (2020)(26) | 32 subjects | 12 weeks; 3 times per week | REx-3 sets of 10 repetitions; once per week AEx- 30 mins; twice week |

morning (08:00–10:00) afternoon (15:00–18:00) |

FPG, VO2max | A significant difference in FPG found reduced in afternoon, VO2 max unaltered. |

| Age:61 ± 5

years old |

||||||

| Gender: male BMI:> 26 kg/m2 |

||||||

| HbA1c: NA | ||||||

| Moholdt et al. (2021)(23) | 25 subjects | 11 days | Day 1-5: HFD Days 6, 8 and 10: 10 x 1 min HIIT Day 7: Moderate intensity (40 min) Day 9: Moderate intensity (60 min) |

morning (06:30) afternoon (18:30) |

CGM, serum metabolites, blood glucose levels | A significant difference seen in CGM, serum metabolites, blood glucose levels in afternoon group. |

| Age:30–45 years old | ||||||

| Gender: male | ||||||

| BMI:27.0–35.0 kg/m2 | ||||||

| HbA1c: NA | ||||||

| M. Savikj et al. (2022)(28) | 15 subjects | 2 weeks; 3 times per week | 3 sets of 6 repetitions HIIT |

morning (08:00) afternoon (16:45) |

HbA1c | No statistically significant difference was seen. |

| Age: 45-68 years old | ||||||

| Gender: male | ||||||

| BMI:22-33 kg/m2 | ||||||

| HbA1c: 6.4% | ||||||

| Table 2: RISK OF BIAS ASSESSMENT | ||||||

| Study Included | Study quality (10) | External validity (3) | Study bias (7) | Confounding and selection bias (6) | Power (1) | Total/ 28 |

| Gomez et al. (2015)(27) | 8 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 19 |

| Savikj et al. (2018)(8) | 10 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 21 |

| Teo et al. (2019)(24) | 8 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 16 |

| Hannemann et al. (2020)(25) | 6 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 11 |

| Mancilla et al. (2020)(26) | 7 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 12 |

| Moholdt et al. (2021)(23) | 9 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 20 |

| M. Savikj et al. (2022)(28) | 7 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 17 |

| Table 3: Results of Recruited Studies | |||||||

| Study | Endpoints | Morning | p-value | Afternoon | p-value | Con | p-value |

| Savikj et al. (2018) (8) | CGM (mmol/l) | 7.7 ± 0.4 | p < 0.1 | 7.5 ± 0.3 | p < 0.05 | _ | _ |

| Gomez et al. (2015) (27) | CGM (mmol/l) | 0.43-0.63 | P = 0.003 | 0.93-1.14 | p ≤ 0.001

p = 0.001 |

_ | _ |

| Moholdt et al. (2021)(23) | CGM (mmol/l) serum metabolites blood glucose levels |

4.9 ± 0.5

28.5 ± 6.1 |

p < 0.05

p = 0.003 |

4.8 ± 0.5

31.2 ± 4.4 |

p=<0.01 | 5.0 ± 0.4

29.0 ± 4.3 |

p < 0.05

_ |

| Mancilla et al. (2020)(26) | FPG (mmol/l) VO2max(ml/kg/min) |

−0.3 ± 1.0 26 ± 4.0 |

_ | 0.5 ± 0.8 26.5 ± 4.5 |

_ | _ | _ |

| Teo et al. (2019)(24) | PPI (pmol·L−1) PPG (mmol·L−1) Fructosamine (effect size) |

0wks 12wks 501 ± 249 342 ± 152 13.07 ± 1.48 11.2 ± 0.86 0.53 0.5 |

p=<0.01

p=<0.01 |

0wks 12wks 409 ± 305 268 ± 132 14.81 ± 3.41 12.44 ± 2.55 0.61 0.32 |

P = .011

p=0.09 |

_ | _ |

| M. Savikj et al. (2022)(28) | HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 46 ± 5 | _ | 46 ± 5 | _ | _ | _ |

| Hannemann et al. (2020)(25) | VO2max(ml/kg/min) OGTT (mg/dL) |

35.8±7.3 94.4±23.9 |

ns ns |

30.1±6.8 86.4±8.3 |

ns ns |

_ | _ |

| (CGM; continuous glucose monitoring, PPI; post-prandial insulin, PPG; post-prandial glucose, FPG; fasting plasma glucose, OGTT; oral glucose tolerance test, ns;- not significant) | |||||||

Discussion:

This systematic review provides evidence that afternoon exercise timings showed a positive impact on different glycemic markers. The studies included in this review discussed different endpoints and concluded the results based on exercise timings (Refer to Table 1). This review emphasizes the critical relation between the circadian rhythm and the external cue of exercise timings. It is well-established that the synchronization of the external environmental cues with the internal circadian rhythm is an important regulator of physiological homeostasis and metabolism.29 Therefore, optimizing the particular exercise timings for the potent non-pharmacological treatment of diabetes should be studied further by researchers.

The optimal timing of exercise remains a subject of debate, yielding mixed results in our review. Some studies advocate for morning exercise, citing favorable outcomes, while others champion afternoon sessions. Interestingly, several trials suggest that the exercise timings have little bearing on glucose decline or stability. However, certain findings from Teo et al. introduce complexities, revealing ambiguous results regarding glycemic control and insulin sensitivity.24 While statistical benefits are elusive between morning and afternoon exercise groups, noteworthy differences emerge within the Type 2 diabetes cohort, hinting at nuanced effects based on timing. The rationale behind differing outcomes lies in circadian modulation of metabolism. Morning exercise coincides with higher cortisol and catecholamine levels, promoting greater fat oxidation and aiding weight management, which can indirectly improve long-term glycemic control. However, insulin sensitivity is generally lower in the morning, potentially limiting immediate glucose uptake after early workouts. In contrast, afternoon or evening exercise occurs when body temperature, muscle enzyme activity, and GLUT-4 expression peak, facilitating superior glucose transport into skeletal muscles. Additionally, enhanced exercise performance and oxygen utilization later in the day may amplify metabolic benefits. Hence, the variability in findings reflects the interplay between circadian biology, hormonal rhythms, and individual metabolic profiles among participants.

Furthermore, the intricate interplay between endocrine hormones and diabetes adds another layer of complexity. Savikj et al. highlight how afternoon High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) impacts parathyroid hormone (PTH) and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels, underscoring the interconnected nature of the endocrine system.8 Additionally, observations of hypoglycemic events during exercise sessions unveil distinct patterns. Morning exercise sessions exhibit fewer hypoglycemic events compared to afternoon sessions, suggesting superior metabolic control and prolonged euglycemia.27

Overall, these findings underscore the crucial importance of considering exercise timing in diabetes management, as it can influence several metabolic outcomes such as fasting plasma glucose, HbA1c levels, insulin sensitivity, lipid metabolism, and oxidative capacity. Aligning physical activity with optimal circadian phases enhances glucose uptake, improves glycemic variability, reduces postprandial glucose spikes, and supports better lipid regulation. Collectively, these physiological improvements contribute to enhanced energy levels, mood stability, sleep quality, and overall functional capacity, thereby improving patients’ well-being and adherence to lifestyle interventions.

As far as we know, this is the first systematic review that has provided crucial insights related to the synchrony of exercise timings according to glucose metabolism. The literature is very limited, highlighting the effect of exercise timings on diabetes management. However, the trials performed on animal models and other epidemiological studies are some great works in the area of circadian rhythm.30 Though the randomized controlled trials that are performed on rodents or whose sample size is other than humans are excluded from this review. As discussed about the sparsity of the literature, the studies included in this review show great variability concerning endpoints and the interventions; however, the exercise timings are mentioned in each recruited study. Furthermore, our research acknowledges the scarcity of gender-diverse trials, with a predominant focus on male participants. Only one randomized controlled trial 24 included a mixed sample of males and females, underscoring the need for broader female gender representation in future studies. Despite these limitations, the findings in this review contribute valuable insights to the existing body of knowledge.

Healthcare professionals and clinical exercise physiologists can consider recommending afternoon exercise sessions for individuals with Type 2 diabetes to enhance glycemic control. This recommendation is supported by accumulating evidence that circadian rhythms influence metabolic and hormonal responses to exercise. During the afternoon, skeletal muscle temperature, enzymatic activity (particularly glycogen synthase and hexokinase), and mitochondrial oxidative capacity are at their peak, which collectively enhance glucose uptake and utilization. Studies such as Savikj et al 8 and Moholdt et al 23 demonstrated significantly greater reductions in mean interstitial glucose and improved insulin sensitivity following afternoon high-intensity or aerobic sessions compared with morning exercise.

Furthermore, insulin sensitivity is typically lower in the early morning due to elevated cortisol and catecholamine levels, which promote hepatic glucose output and transient insulin resistance. As the day progresses, circadian regulation of GLUT-4 translocation and muscle glycogen resynthesis reaches its optimal phase, facilitating more efficient glucose clearance from the bloodstream. These physiological advantages suggest that afternoon exercise better synchronizes with the body’s natural metabolic rhythm, yielding superior glycemic control, reduced glycemic variability, and enhanced overall energy metabolism.

Integrating this timing-based approach into diabetes self-management programs may not only optimize metabolic outcomes but also improve patient adherence, as afternoon sessions often align more conveniently with patients’ daily routines, resulting in sustainable behavioral change and better long-term outcomes.

Future research should aim to conduct larger-scale randomized controlled trials with a focus on gender balance, particularly increasing the representation of female participants as most existing trials have included few or no female participants, limiting the generalizability of findings. Hormonal fluctuations across the menstrual cycle influence insulin sensitivity, glucose metabolism, and energy utilization with estrogen enhancing glucose uptake and fat oxidation, while progesterone may reduce these effects. Addressing this gap will allow the development of gender-specific and more accurate exercise timing recommendations for diabetes management. Studies should also strive to standardize exercise interventions and endpoints to reduce heterogeneity and allow for potential meta-analysis. It is also recommended that future trials assess long-term outcomes of exercise timing on glycemic control and related metabolic parameters.

This review is limited by the small number of eligible RCTs and the heterogeneity among their endpoints, populations, and interventions, which precluded meta-analysis. Most studies focused on male participants, limiting generalizability to the female population. Additionally, the review excluded non-English publications and animal studies, which may have contained relevant insights.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, the findings of this systematic review have focused on how intricate the relationship between the timing of exercise on the muscle clock and the function of glycemic control works. Through a comprehensive analysis of existing literature, it is evident that afternoon timing plays a pivotal role in reducing glycemic parameters to the extent that there is no adverse event taking place in the process. his can be explained by the body’s circadian rhythm, which enhances muscle temperature, enzymatic activity, and insulin sensitivity later in the day. During the afternoon, glucose transporter type-4 (GLUT-4) translocation and muscle glycogen synthesis reach their optimal levels, promoting efficient glucose uptake and utilization. Additionally, hormonal profiles—characterized by lower cortisol and higher insulin responsiveness—create a more favorable metabolic environment for maintaining glucose homeostasis.

Because of these physiological advantages, afternoon exercise tends to improve glycemic variability and energy metabolism without leading to hypoglycemic episodes or cardiovascular strain, which are more likely during morning sessions when cortisol and sympathetic activity are high. Hence, the timing of exercise directly contributes to both the efficacy and safety of glycemic regulation in individuals with Type 2 diabetes.

Future endeavors should aspire towards monumental strides, embracing larger sample sizes and a robust cadre of randomized control trials, particularly among female populations. This concerted effort aims to forge an unassailable foundation for unbiased and conclusive associations.

As the research landscape continues its evolutionary trajectory, the synthesis of current evidence tantalizingly hints at the transformative potential of synchronizing exercise routines with circadian rhythms. This paradigm shift not only promises to optimize performance but also heralds profound metabolic enhancements and fosters holistic musculoskeletal well-being, paving the way for a brighter future in the realm of health and fitness.

Acknowledgement:

The authors extend their heartfelt appreciation to Mr. Faisal Qureshi and Dr. Sonya Arshad for their valuable contributions to our systematic review. Their expertise, dedication, and collaborative spirit have significantly enriched the quality and depth of this research.

References:

- Parr EB, Heilbronn LK, Hawley JA. A time to eat and a time to exercise. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2020; 48:4–10. doi:10.1249/JES.0000000000000207

- Saeedi P, Petersohn I, Salpea P, Malanda B, Karuranga S, Unwin N, et al. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9 edition.

- Zimmet P, Alberti K, Stern N, Bilu C, El-Osta A, Einat H, et al. The Circadian Syndrome: is the Metabolic Syndrome and much more!

- Bird SR, Hawley JA. Update on the effects of physical activity on insulin sensitivity in humans. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2017;2: e000143. doi:10.1136/bmjsem-2016-000143

- Berman LJ, Weigensberg Mj Fau – Spruijt-Metz D, Spruijt-Metz D. Physical activity is related to insulin sensitivity in children and adolescents, independent of adiposity: a review of the literature.

- Haxhi J, Scotto di Palumbo A Fau – Sacchetti M, Sacchetti M. Exercising for metabolic control: is timing important?

- Martínez-Montoro JA-O, Benítez-Porres JA-O, Tinahones FJ, Ortega-Gómez AA-O, Murri M. Effects of exercise timing on metabolic health.

- Savikj M, Gabriel BM, Alm PS, Smith J, Caidahl K, Björnholm M, et al. Afternoon exercise is more efficacious than morning exercise at improving blood glucose levels in individuals with type 2 diabetes: a randomised crossover trial.

- Ashmore A. Timing resistance training: Programming the muscle clock for optimal performance: Human Kinetics; 2019.

- Mayeuf-Louchart A, Staels B, Duez H. Skeletal muscle functions around the clock. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism. 2015; 17:39-46.

- Zylka MJ, Shearman LP, Weaver DR, Reppert SM. Three period Homologs in Mammals: Differential Light Responses in the Suprachiasmatic Circadian Clock and Oscillating Transcripts Outside of Brain. Neuron. 1998; 20:1103-10.

- Schroder EA, Esser KA. Circadian Rhythms, Skeletal Muscle Molecular Clocks, and Exercise. 2013; 41:224-9.

- Harfmann BD, Schroder EA, Esser KA. Circadian Rhythms, the Molecular Clock, and Skeletal Muscle. Journal of Biological Rhythms. 2015; 30:84-94.

- Martin RA, Esser KA. Time for Exercise? Exercise and Its Influence on the Skeletal Muscle Clock. Journal of Biological Rhythms. 2022; 37:579-92.

- Chtourou H, Souissi N. The effect of training at a specific time of day: a review. J Strength Cond Res. 2012; 26:1984–2005. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e31825770a7

- Facer-Childs E, Brandstaetter R. The impact of circadian phenotype and time since awakening on diurnal performance in athletes.

- Hatamoto Y, Goya R, Yamada Y, Yoshimura E, Nishimura S, Higaki Y, et al. Effect of exercise timing on elevated postprandial glucose levels.

- Hetherington-Rauth MA-O, Magalhães JP, Rosa GB, Correia IR, Carneiro T, Oliveira EC, et al. Morning versus afternoon physical activity and health-related outcomes in individuals with type 2 diabetes.

- van der Velde JA-O, Boone SA-O, Winters-van Eekelen EA-O, Hesselink MA-O, Schrauwen-Hinderling VA-OX, Schrauwen PA-OX, et al. Timing of physical activity in relation to liver fat content and insulin resistance.

- Heden TD, Kanaley JA. Syncing Exercise with Meals and Circadian Clocks.

- Page MA-O, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews.

- Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions.

- Moholdt TA-O, Parr EA-O, Devlin BA-O, Debik JA-O, Giskeødegård GA-O, Hawley JA-O. The effect of morning vs evening exercise training on glycaemic control and serum metabolites in overweight/obese men: a randomised trial.

- Teo SYM, Kanaley JA, Guelfi KJ, Marston KJ, Fairchild TJ. The Effect of Exercise Timing on Glycemic Control: A Randomized Clinical Trial.

- Hannemann JA-O, Laing A, Glismann K, Skene DJ, Middleton B, Staels B, et al. Timed physical exercise does not influence circadian rhythms and glucose tolerance in rotating night shift workers: The EuRhythDia study.

- Mancilla R, Brouwers B, Schrauwen-Hinderling VB, Hesselink MA-O, Hoeks J, Schrauwen PA-OX. Exercise training elicits superior metabolic effects when performed in the afternoon compared to morning in metabolically compromised humans.

- Gomez AM, Gomez C, Aschner P, Veloza A, Muñoz O, Rubio C, et al. Effects of performing morning versus afternoon exercise on glycemic control and hypoglycemia frequency in type 1 diabetes patients on sensor-augmented insulin pump therapy.

- Savikj M, Stocks B, Sato S, Caidahl K, Krook A, Deshmukh AS, et al. Exercise timing influences multi-tissue metabolome and skeletal muscle proteome profiles in type 2 diabetic patients – A randomized crossover trial.

- Bennett S, Sato S. Enhancing the metabolic benefits of exercise: is timing the key? Front Endocrinol. 2023; 14:987208. doi:10.3389/fendo.2023.987208

- Pendergrast LA, Lundell LS, Ehrlich AA-O, Ashcroft SP, Schönke M, Basse AA-O, et al. Time of day determines postexercise metabolism in mouse adipose tissue.

| Copyright Policy

All Articles are made available under a Creative Commons “Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International” license. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/). Copyrights on any open access article published by Journal Riphah college of Rehabilitation Science (JRCRS) are retained by the author(s). Authors retain the rights of free downloading/unlimited e-print of full text and sharing/disseminating the article without any restriction, by any means; provided the article is correctly cited. JRCRS does not allow commercial use of the articles published. All articles published represent the view of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of JRCRS. |