Original Article: JRCRS.2025:13(3):179-185

10- Level of perceived stress among undergraduate physiotherapy students with primary dysmenorrhea in Sialkot, Pakistan – A Cross Sectional Study

Kainat Shahbaz1, Esha Ali2, Maham Shahbaz3, Iqra Tul Hussain4

1 2 3 House Officer, Imran Idrees Teaching Hospital, Sialkot, Pakistan

4 Senior Lecturer, Imran Idrees Teaching Hospital, Sialkot, Pakistan

Full-Text PDF DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.53389/JRCRS.2025130310

Abstract:

Background: Menstrual pain often caused by prostaglandins, triggering uterine contractions is named as Primary Dysmenorrhea. Perceived stress is stated as an individual’s subjective assessment of the degree to which they feel overwhelmed or unable to cope with the demands of life.

Objective: To determine the level of perceived stress among undergraduate physiotherapy female students with primary dysmenorrhea in Sialkot, Pakistan.

Methodology: This Cross-sectional study included 232 females with primary dysmenorrhea, selected using Simple non-random sampling technique. Inclusion criteria was age (18-25 years), women with normal menstrual cycle lasting between 21 to 35 days, low back pain that begins one day before the menstrual cycle and lasts for 6-12 hours after the start of menstrual cycle, and leads to 3 days of bleeding in last 3 menstrual cycles whereas polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), amenorrhea, use of oral contraceptives, use of intrauterine devices, pregnancy and secondary dysmenorrhea were excluded from the study. The outcome measuring tool was Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10). The data was analyzed using SPSS software 22 and interpreted as frequencies and percentages.

Results: Out of 232 participants the mean age was (21.34± S.D 1.49 years). The majority of the participants were unmarried (N=206, 88.8%). Most of the participants (N=138, 59.5%) had normal Body Mass Index, (N=131, 56.5%) had healthy diet with maximum sleep duration of 12 hours. Most of the participants had 3-5 days of menstrual bleeding (N=188, 81.0%), moderate menstrual flow (N=182, 78.4%), 21-35 days of menstrual cycle length (N=169, 72.8%) and menarche at the age of 13 years (N=57, 24.6%). The Participant’s mean score of perceived stress scale was (22.10± S.D 5.92).

Conclusion: The study concluded that students with primary dysmenorrhea had moderate level of perceived stress.

Keywords: Menarche, Primary Dysmenorrhea, Perceived Stress

Introduction:

Dysmenorrhea exerts influence on many women during their menstrual cycles. The incident of menstrual pain rangeds from 45% to 95%, with 2% to 29% experiencing severe pain.1 In Pakistan, the frequency of menstrual pain among medical students in Mirpur, Azad Kashmir, was found to be 56.1%.2 Normal menstruation was referred to the cyclic bleeding from fundus between pubescence and menopause. It embraces four main aspects: the frequency, regularity, duration, and volume of bleeding episodes. Additionally, women may experience other symptoms like pain, anxiety and fatigue.3 In the early menstrual cycle, estrogen stimulates the growth of the endometrial lining, supporting its proliferation and maturation for potential pregnancy. In the luteal phase, progesterone, stimulated by LH, prepares the corpus luteum and endometrium for possible embryo implantation.4 Primary dysmenorrhea is a common and significant condition, especially among female undergraduates, warranting further research. It is characterized by intense lower abdominal pain before or during menstruation and is classified as primary or secondary. Primary dysmenorrhea, with no identifiable gynaecological cause, is linked to imbalanced prostanoid and eicosanoid release, leading to abnormal uterine contractions. Secondary dysmenorrhea, however, arises from pelvic conditions like endometriosis or ovarian cysts. The pathogenesis of primary dysmenorrhea involves excessive production of uterine prostaglandins (PGF2α and PGE2) triggered by progesterone withdrawal in the late luteal phase, causing increased myometrial contractions, vasoconstriction, and uterine ischemia, resulting in pain and systemic symptoms. Elevated vasopressin levels during menstruation may also worsen uterine contractions, hypoxia, and pain severity.5 The etiology of PD includes brain abnormalities and metabolic factors, with studies suggesting higher serum nitric oxide (NO) levels and lower homocysteine levels in PD patients.6 Primary dysmenorrhea is diagnosed clinically by reviewing the patient’s medical history and identifying symptoms such as abdominal or pelvic cramps (sometimes radiating to the legs), lower back pain, headache, nausea, vomiting, or fatigue lasting 6–12 hours in child bearing age (45-90% of females) and has no other organic cause.7 Despite not being life-threatening, dysmenorrhea significantly affects women’s quality of life, impairing relationships, work performance, and daily activities.8 Previous researches show that dysmenorrhea is related with stress and affects the quality of life in female undergraduates. Stress is characterized as a state of imbalance, countered by a range of physiological and behavioural reactions aimed at restoring or maintaining homeostasis.9 When we encounter stress, two physiological systems are activated. The first is the sympathetic adrenal medullary1 system. Another mechanism is that hypothalamus reacts to stress by releasing a hormone called corticotrophin releasing factor (CRF).10 There are several types of stress and perceived stress is one of them which is defined as how individuals evaluate the level of stress in their lives, based on their subjective interpretation of various life circumstances and events.11 A significant portion of female undergraduate students encountered stress levels ranging from moderate to severe which is thought to be related with the prevalence of primary dysmenorrhea in them.12 Other factors linked to dysmenorrhea include emotional eating and BMI abnormalities. Emotional eating, which involves eating in response to emotional states, is strongly correlated with high stress levels and BMI. Stress, in turn, influences dietary habits and can contribute to weight gain, overweight, and obesity, raising BMI levels.13 Research indicates that socio-demographic factors such as educational level, socioeconomic status, neighbourhood characteristics, and gender were associated with perceived stress in students.14 In past researches there was insufficient focus on understanding the causal role of negative emotions in linked with dysmenorrhea.15 Limited studies indicate a link between prevalent levels of perceived stress with poor diet quality which underscores the need for further research.16 Therefore this study aimed to determine the level of perceived stress in primary dysmenorrhea among undergraduate physiotherapy students in Sialkot.

Methodology:

This cross-sectional study design was conducted from April to July 2024 in Sialkot, Pakistan after getting approval from the Institutional Ethical Review Committee of Imran Idrees Institute of Rehabilitation Sciences, Sialkot (IERC), IIIRS/DPT/PRI/IRB-794. The sample size of 232 was calculated using Epi-tool software, with a 0.95 confidence level, a 0.5 margin of error, a 0.05 desired precision of estimate and an estimated true proportion of 0.78.17 Female physiotherapy students with primary dysmenorrhea, enrolled between 2019 and 2024, were selected through a simple non-random sampling technique from private institutes in Sialkot, including Sialkot Medical College, University of Management and Technology, University of Sialkot, Islam Medical College, and Sialkot College of Physical Therapy. The inclusion criteria was participants aged 18-25, regular menstrual cycle of 21-35 days, experiencing low back pain that starts a day before menstruation lasting 6-12 hours, and three days of bleeding in the last three cycles.18 Exclusion criteria included women with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), amenorrhea, and pregnancy, those using oral contraceptives or intrauterine devices and secondary dysmenorrhea (having clinical history of intrauterine bleeding, fibroids, recurrent pelvic infections).

Before data collection, permission was obtained from the institutes, and female students with primary dysmenorrhea provided informed consent. Data confidentiality was ensured. Once consent was received, data was collected using the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10), developed by Cohen et al., to assess perceived stress levels. The PSS-10 measures the extent to which an individual experienced feeling of life being out of control, unpredictable, and overwhelming in the past month. The reliability and validity of Perceived stress scale was Cronbach’s alpha value =0.17-0.91.19 The PSS-10 comprises two subscales; Perceived helplessness (item 1, 2, 3, 6, 9, 10) was evaluated an individual’s perception of limited control over their circumstances or their capacity to regulate their emotions and responses. Lack of Self-efficacy (4, 5, 7, and 8) was assessed an individual’s perception of struggling to cope with difficulties.

The PSS-10 is a questionnaire with 10 items rated on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from ‘Never’ to ‘Very Often.’ Scoring follows this scale: Never = 0, Almost Never = 1, Sometimes = 2, Fairly Often = 3, Very Often = 4. To calculate the total score, reverse the scores for questions 4, 5, 7, and 8 as follows: 0 = 4, 1 = 3, 2 = 2, 3 = 1, and 4 = 0. The individual item scores were summed to get a total score ranging from 0 to 40. Scores indicate from0 to 13 as low stress, 14 to 25 as moderate stress and 26 to 40 as high perceived stress levels.

The data was analysed using SPSS software version 22. Frequencies and percentages were used for data evaluation, and the results were displayed in tables and graphical illustrations.

Results

The results showed that the mean age of participants was (21.34 ± 1.49 years). Among the 232 participants, most were unmarried (N = 206, 88.8%). BMI category results indicated that the majority had a normal BMI (N = 138, 59.5%), while 58 (25.0%) were underweight. Most participants belonged to the middle socioeconomic group (N = 207, 89.2%) and consumed healthy food (N = 131, 56.5%). The mean sleep duration was 7.46 ± 1.66 hours, with 136 participants (N= 136, 58.6%) reporting adequate sleep over the past three months. Regarding menstrual characteristics, most reported 3–5 days of bleeding (N = 188, 81.0%) with a moderate flow volume (N = 182, 78.4%), and a cycle length of 21–35 days (N = 169, 72.8%). The most common age at menarche was 13 years (N= 57, 24.6%), (Table I showed demographics and menstrual cycle characteristics among participants).

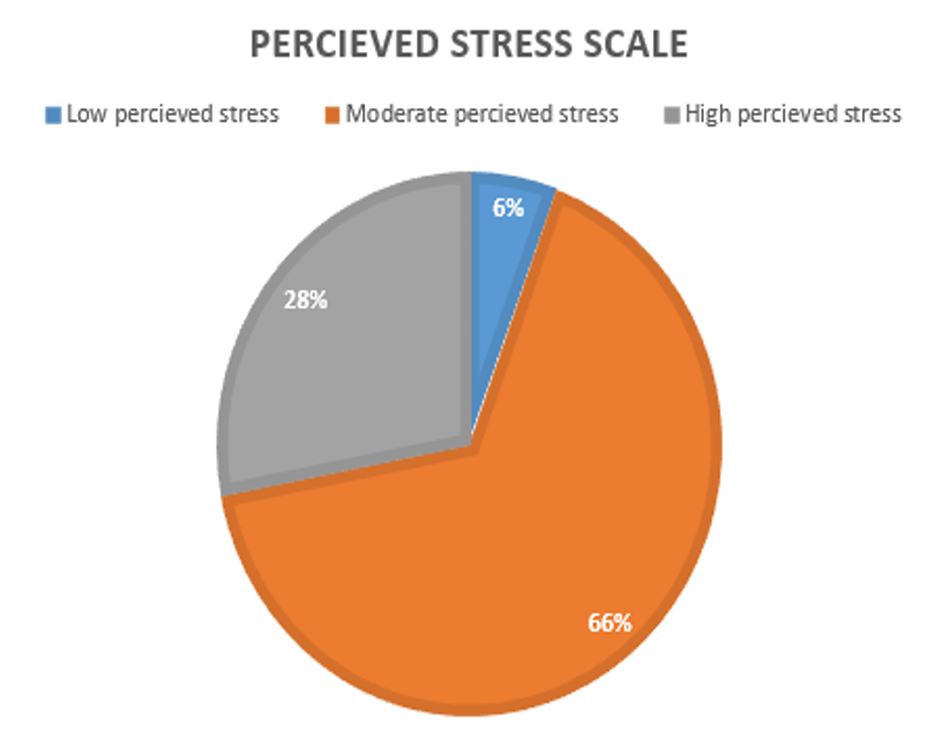

The mean Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) score was 22.10 ± 5.92. The total score on PSS ranges from 0 to 40. Most participants (N = 154, 66.4%) had moderate perceived stress level ranging from (14-25 score) on PSS, participants (N = 65, 28%) had high perceived stress level ranging (26-40 score) on PSS whereas (N = 13, 5.6%) of respondents had low perceived stress level ranging (0-13 score) on PSS.

The Perceived stress scale questionnaire results showed that out of the 232 participants, (N= 84, 36.2%) sometimes felt upset by unexpected events, and (N=77 ,33.2%) sometimes felt unable to control important aspects of their lives over the past month. Additionally, 28.9% (N=67) sometimes felt nervous and stressed. Additionally, 33.6% of participants (N=78) Confidence in handling personal problems, while 36.2%(N=84) felt that things sometimes went their way. Regarding coping, 34.5%(N=80) could sometimes manage responsibilities, and 31.0%(N=72) occasionally controlled irritations. Similarly, 35.8%(N=83) sometimes felt on top of things. Some also reported occasional anger over uncontrollable events (N = 66, 28.4%) and a sense that difficulties were piling up (N = 69, 29.7%), (Table II showed frequency distribution of PSS among participants).

The bar chart analysis results showed that the majority of the participants with primary dysmenorrhea had moderate stress levels (N=154, 66.4%), while a small portion had low stress levels (N=13, 6.4%) (Figure I).

Figure I: Grading of Perceived Stress among participants (N=232)

| Table I. Demographics and Menstrual Cycle characteristics of the participants (N=232) | ||

| Marital status | Frequency (N) | Percentage (%) |

| Unmarried | 206 | 88.8% |

| Married | 26 | 11.2% |

| Body Mass Index | ||

| Overweight | 36 | 15.5% |

| Normal | 138 | 59.5% |

| Underweight | 58 | 25.0% |

| Socio-Economic Status | ||

| Low class | 8 | 3.4% |

| Middle class | 207 | 89.2% |

| High class | 17 | 7.3% |

| Eating Habits | ||

| Healthy food | 131 | 56.5% |

| Junk food | 101 | 43.5% |

| Academic Year of The Participants | ||

| 1st year | 33 | 14.2% |

| 2nd year | 31 | 13.4% |

| 3rd year | 48 | 20.7% |

| 4th year | 66 | 28.4% |

| 5th year | 54 | 23.3% |

| Menstrual Cycle Characteristics

(Days of Bleeding) |

||

| Less than 2 days | 7 | 3.0% |

| 3-5 days | 188 | 81.0% |

| More than 7 days | 37 | 15.9% |

| Menstrual Flow Volume | ||

| Spotting | 5 | 2.2% |

| Moderate flow | 182 | 78.4% |

| Heavy flow | 42 | 18.1% |

| Very heavy flow | 3 | 1.3% |

| Length of Menstrual Cycle (Per Month) | ||

| Less than 21 days | 39 | 16.8% |

| 21-35 days | 169 | 72.8% |

| More than 35 days | 24 | 10.3% |

| Age of Menarche | ||

| 10 years | 13 | 5.6% |

| 11 years | 20 | 8.6% |

| 12 years | 37 | 15.9% |

| 13 years | 57 | 24.6% |

| 14 years | 56 | 24.1% |

| 15 years | 30 | 12.9% |

| 16 years | 19 | 8.2% |

| Table II: Frequency Distribution of Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) among participants N=232 | ||

| 1. In the last month, how often have you been upset because of something that happened unexpectedly? | ||

| Never* | Frequency (N) | Percentage (%) |

| 20 | 8.6 % | |

| Almost Never | 21 | 9.1 % |

| Sometimes | 84 | 36.2 % |

| Fairly Often | 40 | 17.2 % |

| Very Often | 67 | 28.9 % |

| 2. In the last month, how often have you felt that you were unable to control the important things in your life? | ||

| Never | 26 | 11.2 % |

| Almost Never | 27 | 11.6 % |

| Sometimes | 77 | 33.2 % |

| Fairly Often | 53 | 22.8 % |

| Very Often | 49 | 21.1 % |

| 3. In the last month, how often have you felt nervous and stressed? | ||

| Never | 9 | 3.9 % |

| Almost Never | 27 | 11.6 % |

| Sometimes | 67 | 28.9 % |

| Fairly Often | 66 | 28.4 % |

| Very Often | 63 | 27.2 % |

| 4. In the last month, how often have you felt confident about your ability to handle your personal problems? | ||

| Never | 14 | 6.0 % |

| Almost Never | 40 | 17.2 % |

| Sometimes | 78 | 33.6 % |

| Fairly Often | 53 | 22.8 % |

| Very Often | 47 | 20.3 % |

| 5. In the last month, how often have you felt that things were going your way? | ||

| Never | 30 | 12.9 % |

| Almost Never | 55 | 23.7 % |

| Sometimes | 84 | 36.2 % |

| Fairly Often | 41 | 17.7 % |

| Very Often | 22 | 9.5 % |

| 6. In the last month, how often have you found that you could not cope with all the things that you had to do? | ||

| Never | 24 | 10.3 % |

| Almost Never | 48 | 20.7 % |

| Sometimes | 80 | 34.5 % |

| Fairly Often | 46 | 19.8 % |

| Very Often | 34 | 14.7 % |

| 7. In the last month, how often have you been able to control irritations in your life? | ||

| Never | 21 | 9.1 % |

| Almost Never | 46 | 19.8 % |

| Sometimes | 72 | 31.0 % |

| Fairly Often | 63 | 27.2 % |

| Very Often | 30 | 12.9 % |

| 8. In the last month, how often have you felt that you were on top of things? | ||

| Never | 36 | 15.5 % |

| Almost Never | 54 | 23.3 % |

| Sometimes | 83 | 35.8 % |

| Fairly Often | 32 | 13.8 % |

| Very Often | 27 | 11.6 % |

| 9. In the last month, how often have you been angered because of things that happened that were outside of your control? | ||

| Never | 14 | 6.0 % |

| Almost Never | 32 | 13.8 % |

| Sometimes | 66 | 28.4 % |

| Fairly Often | 62 | 26.7 % |

| Very Often | 58 | 25.0 % |

| 10. In the last month, how often have you felt difficulties were piling up so high that you could not overcome them? | ||

| Never | 19 | 8.2 % |

| Almost Never | 45 | 19.4 % |

| Sometimes | 69 | 29.7 % |

| Fairly Often | 52 | 22.4 % |

| Very Often | 47 | 20.3 % |

| Total Score: 40

Mean Score: 22.10 ± 5.92 |

||

| *0=Never, 1=Almost Never, 2= Sometimes, 3= Fairly Often, 4= Very Often | ||

Discussion:

The current study found that most participants (N= 154, 66.4%) with primary dysmenorrhea had moderate stress levels. Similarly, Deemah Alateeq et al conducted a study in Saudi Arabia in the year 2022. This study explores the occurrence of dysmenorrhea and its link to depression among university students in Saudi Arabia, concluding that those with severe dysmenorrhea face a higher risk of developing depression compared to their peers.20 In another study by Manisha et al. (2022), 56 females were surveyed. A majority, specifically 47 individuals, reported experiencing moderate stress with primary dysmenorrhea[18]. Moreover, our results aligned with the study by Iqra tul Hussain et al. (2023), which reported varying stress levels related to menstruation. Out of 71 participants, 33 (46.5%) described their stress as moderate, indicating notable but manageable discomfort affecting daily life.21 But in contrast to the findings of our study the study documented by Jain, Prashant et al. in 2023 found lower levels of perceived stress in the late follicular phase.22 And a study conducted by Periasamy, Panneerselvam et al. in 2021concluded that that high stress levels are caused by substantial menstrual flow 23 whereas our study findings reported a moderate degree of felt stress and mild menstruation.

Similar findings were reported by Naser Al-Husban et al. (2022), who found no statistically significant correlations between severe dysmenorrhea and variables such as age, Body Mass Index (BMI), weekly study hours, and age at menarche.24 Out of 232 participants, 46 reported almost never being able to control irritation. Similarly, Rediet Tekalign et al. (2020) found that 54.6% of participants experienced irritability, significantly impacting their interpersonal relationships and daily interactions.25

Furthermore, a study conducted by Verena Thomann, Nadya Gomma, Marina Stang et al. (2025) among females addressing the factors of negative expectations and related emotions producing nocebo effects which contributes to recurring menstrual pain (primary dysmenorrhea). This study concluded pain expectations and negative anticipatory emotions may act as associated factors in heightened pain threshold and sensitivity among women with severe menstrual pain compared to those with little or no pain. Findings of the study suggest that cognitive-emotional states including strong pain anticipation and adverse emotions, worsen the perception of menstrual pain in primary dysmenorrhea likewise this current study concluded moderate perceived level of stress among females with primary dysmenorrhea.26

The limitations of this study were that the data was collected from Sialkot only which could affect the generalizability of the results. For further studies, it is recommended to explore the association of menarche, menstrual cycle length and symptoms severity on stress levels and dysmenorrhea experiences in physiotherapy students. Future research could also explore the comparative effects of perceived stress on primary versus secondary dysmenorrhea, to better understand their differing physiological and psychological impacts.

Conclusion:

The study concluded that undergraduate physiotherapy students in Sialkot, Pakistan with primary dysmenorrhea had experienced moderate levels of perceived stress beholding normal body mass indices and moderate menstrual flow volume with 3-5 bleeding days per cycle.

References:

- Karout, S., et al., Prevalence, risk factors, and management practices of primary dysmenorrhea among young females. BMC women’s health, 2021. 21: p. 1-14.

- Adil, R. and U. Zaigham, Prevalence of primary dysmenorrhoea and its effect on instrumental activities of daily living among females from Pakistan. Physiotherapy Quarterly, 2021. 29(4): p. 65-69.

- Critchley, H.O., et al., Menstruation: science and society. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology, 2020. 223(5): p. 624-664.

- Thiyagarajan, D.K., H. Basit, and R. Jeanmonod, Physiology, menstrual cycle, in StatPearls [Internet]. 2022, StatPearls Publishing.

- Szmidt, M.K., et al., Primary dysmenorrhea in relation to oxidative stress and antioxidant status: a systematic review of case-control studies. Antioxidants, 2020. 9(10): p. 994.

- Nunez-Troconis, J., D. Carvallo, and E. Martínez-Núñez, Primary Dysmenorrhea: pathophysiology. Investigación Clínica, 2021. 4: p. 378-406.

- Wang, Y.-L. and H.-L. Zhu, The prevalence and associated risk factors of primary dysmenorrhea among women in Beijing: a cross-sectional study. Scientific Reports, 2025. 15(1): p. 5003.

- Al-Matouq, S., et al., Dysmenorrhea among high-school students and its associated factors in Kuwait. BMC pediatrics, 2019. 19: p. 1-12.

- Tsigos, C., et al., Stress: endocrine physiology and pathophysiology. Endotext [Internet], 2020.

- O’Connor, D.B., J.F. Thayer, and K. Vedhara, Stress and health: A review of psychobiological processes. Annual review of psychology, 2021. 72: p. 663-688.

- Aslan, I., D. Ochnik, and O. Çınar, Exploring perceived stress among students in Turkey during the COVID-19 pandemic. International journal of environmental research and public health, 2020. 17(23): p. 8961.

- Graves, B.S., et al., Gender differences in perceived stress and coping among college students. PloS one, 2021. 16(8): p. e0255634.

- Barcın-Güzeldere, H.K. and A. Devrim-Lanpir, The association between body mass index, emotional eating and perceived stress during COVID-19 partial quarantine in healthy adults. Public Health Nutrition, 2022. 25(1): p. 43-50.

- Pangtey, R., et al., Perceived stress and its epidemiological and behavioral correlates in an urban area of Delhi, India: a community-based cross-sectional study. Indian journal of psychological medicine, 2020. 42(1): p. 80-86.

- Lee, H. and J. Kim, Direct and Indirect Effects of Stress and Self-Esteem on Primary Dysmenorrhea in Korean Adolescent Girls: A Cross-Sectional Survey Study. Iranian Journal of Public Health, 2024. 53(1): p. 116-125.

- Khaled, K., et al., Perceived stress and diet quality in women of reproductive age: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrition journal, 2020. 19(1): p. 1-15.

- Ashraf, T., et al., Prevalence of dysmenorrhea and impact on young medical students; a cross sectional study on students of medical colleges of Lahore, Pakistan. Rawal Medical Journal, 2020. 45(2): p. 430-3.

- Tiwari, M., et al., Association of primary dysmenorrhea with stress and BMI among undergraduate female students-a cross sectional study. Turkish Journal of Physiotherapy and Rehabilitation, 2022. 32(3): p. 19049-19057.

- Mozumder, M.K., Reliability and validity of the Perceived Stress Scale in Bangladesh. Plos one, 2022. 17(10): p. e0276837.

- Alateeq, D., et al., Dysmenorrhea and depressive symptoms among female university students: a descriptive study from Saudi Arabia. The Egyptian Journal of Neurology, Psychiatry and Neurosurgery, 2022. 58(1): p. 106.

- Hussain, I.T., A. Batool, and A. Iftikhar, Association Between Premenstrual Tension Syndrome and Menstruation Distress with Physical Activity. THE SKY-International Journal of Physical Education and Sports Sciences (IJPESS), 2023. 7: p. 11-20.

- Jain, P., et al., Correlation of perceived stress with monthly cyclical changes in the female body. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 2023. 12(11): p. 2927-2933.

- Periasamy, P., et al., Association of menstrual patterns with perceived stress score in college-going female students of a South Indian town. Apollo Medicine, 2021. 18(2): p. 76-79.

- Al-Husban, N., et al., The influence of lifestyle variables on primary dysmenorrhea: a cross-sectional study. International journal of women’s health, 2022: p. 545-553.

- Tekalign, R., F. Adugna, and M. Daba, Assessment of dysmenorrhea and its associated factors among female medical students of st. Paul’s hospital millennium medical college, addis ababa, ethiopia: an institution based cross sectional study. Ethiopian Journal of Reproductive Health, 2020. 12(4): p. 10-10.

- Thomann, V., et al., Exploring the role of negative expectations and emotions in primary dysmenorrhea: insights from a case-control study. BMC Women’s Health, 2025. 25(1): p. 241.